After disrupting iTunes, Spotify demands a free ride from Apple's App Store

Music streaming service Spotify has elevated its disputes with Apple into a full blown anti-trust complaint filed with the European Commission. But Spotify’s public case, as detailed on its website, is misleading and covers up the basic reality that Spotify wants to do business at Apple’s expense without paying for it.

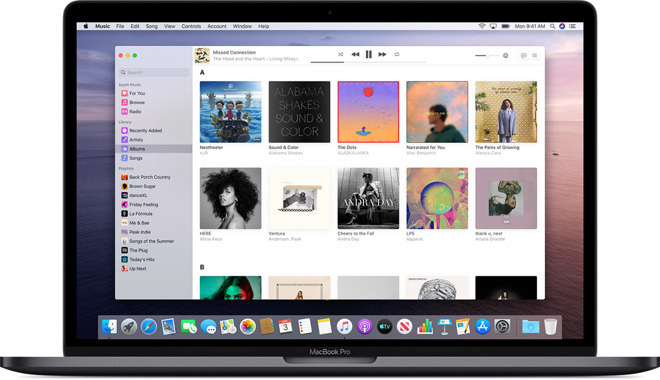

Spotify claims Apple owes it free, unrestricted access to the App Store

Can a first party compete with third parties?

In a blog posting, Spotify’s founder and CEO Daniel Ek touched on some grievances the company has with Apple’s App Store policies but provided scant details backing up the general complaints it presented to the public.

Ek stated that "Apple has introduced rules to the App Store that purposely limit choice and stifle innovation at the expense of the user experience—essentially acting as both a player and referee to deliberately disadvantage other app developers."

That line is reminiscent of a parallel concept presented by U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren, who recently floated the idea that Apple should not be able to run the App Store platform while also serving its own first-party apps or services on it, such as Apple Music.

There certainly are huge advantages for Apple to have and control its own App Store. That’s particularly so given that Apple developed security to block the installation of "side-loaded" apps (outside of web apps, which are functionally limited) from running on iOS devices.

There simply isn’t a way to compete with Apple in "iOS app stores," the same way there isn’t any way to put targeted ads on Facebook with paying Facebook, or any way to sell products on Amazon’s platform without following Amazon’s rules (which include having Amazon’s own products potentially competing with your own).

The only way to really "compete against the App Store" would be to create an entire mobile platform, which is such a huge task that’s so expensive and difficult that not even Microsoft’s Windows Phone or Samsung’s Tizen could pull off one successfully. The only thing remotely competive to the iOS App Store is Android Google Play and Chinese AOSP stores.

In building a secure software store for iOS users, Apple created something of incredible value that didn’t exist before. And over the past decade, Apple has worked to protect its own interests--which include the interests of its customers--by creating rules that prevent third parties from using its store to make money without paying a cut to support the App Store's operation.

Origins of the App Store: when Apple was the Spotify

Spotify’s portrayal of the history of iOS apps on its "Time to Play Fair" complaint site is simplified to the point of being false. It states that in 2007 at Phone’s launch, "At first, Apple does not allow outside apps," but then with the opening of the App Store, "Apple decides to open up the App Store to outside app developers and lures them in by the hundreds."

It’s useful to remember that the origin of the iOS App Store was actually iPod’s iTunes Store—a market Apple created at significant cost and risk, initially with the goal of preventing much larger prevailing competitors (Sony and Microsoft) from preventing Mac users from being able to buy commercial music at all, outside of their rules and restrictions and fees.

Microsoft and Sony each wanted to own access to recorded music, and sold DRM songs tied to their own licensed hardware. If Apple back then had played the role of Spotify today—demanding free access to the music platforms that Microsoft and Sony had built—it would likely never have made any progress in the music business at all, and probably wouldn’t still be around.

Instead of demanding that Microsoft and Sony give Apple a free ride so as to create a "fair and open playing field," Apple worked to create its own playing field. That required developing relationships with record labels and convincing them to also allow it to sell their music in iTunes. This took years of efforts—often involving tense negotiations—and continued for years as a "break even" operation.

On the other end, Apple also had to court customers. Attracting enough buyers away from Sony players and Windows PCs to its own iTunes, iPods and Macs was so exceptionally difficult and risky that nobody believed it could even be possible. Yet Apple successfully built its music business from both ends, against all odds, fairly and without ripping off either musicians, labels or listeners.

Apple began selling music, then videos and eventually TV and movies—all of which were a huge leap away from the company’s existing core competencies in building and selling hardware computing platforms. Even at the height of iPod sales, Apple’s iTunes Store continued to barely make any profit at all, with all of its revenues essentially being reinvested, Amazon style, into making the iTunes Store better. That included an experiment in making and distributing mobile software, initially "iPod Games," starting in 2005.

By then, Apple’s iTunes Store had grandly eclipsed the efforts of Microsoft PlaysForSure and Sony in selling music, and grounded Apple as a primary music vendor. But despite its size and influence over the music industry—created at great cost and effort and risk over several years—Apple’s position in music was then eroded by a new trend in music streaming, a business pioneered by Spotify.

Spotify used the iOS App Store to rapidly expand its business on mobiles

Spotify made its money by leaching music-listening customers away from iTunes the same way that Apple had sucked its own customers away from Microsoft and Sony by offering them more value for less money.

But rather than selling downloads and returning most of the proceeds to music labels and their artists in the model of Apple’s iTunes Store, Spotify allowed listeners to access a huge library of tracks at a minimal subscription fee, which paid back a tiny per-play royalty to the labels and their artists. It also allowed users to listen for free on an unpaid tier, which screwed over musicians even more.

The App Store turns the tables back for Apple vs. Spotify

Spotify actually launched its service in 2008, targeting desktop PC users. It rapidly expanded to the new iOS App Store that Apple opened that same year. Spotify’s historical revisionism insists that Apple didn’t initially allow apps, but that’s not true.

Apple launched iPhone in 2007 with a web browser capable of running basic web apps. However, both users and developers recognized that native apps—just like Apple’s own Mail, Safari and iTunes—would be far superior to the experience of a web app on a phone. That took extra time to finish, as it required a thoughtful series of guidelines, rules and policies that would prevent abusive behavior, malware, spying, and other problems that had already become problematic on desktop PCs.

Web apps were already designed with some security in mind, given that they were designed to run on an inherently insecure platform, but native apps on Windows and Macs didn’t really have this.

On mobile devices equipped with GPS, cameras and microphones, such privacy and security issues would get much worse without some regulation of what developers were allowed to do. Apple’s App Store policies incrementally unfolded as these problems were identified and strategies were created to contain them.

The result is that ten years later, Apple’s App Store is the only place that has attracted anything close to 800 million affluent users who care about their privacy and security. Google Play remains a Wild West mess of junkware, spying, and exploitation. Outside of Google, other Android stores are downright toxic cesspools of molten lava, where users are scammed and defrauded and spied upon constantly.

The App Store didn’t open itself. It cost Apple massive resources to get off the ground and it continues to require incredible resources globally to operate. And yet, Apple still offers access to its store to third-party developers for free, charging fees only when they make money distributing their software or selling subscription services. And recall that selling software is an exceptionally high margin business.

Spotify now takes issue with the fact that it costs money to make money in the App Store. And rather than viewing Apple’s marketplace as a cost-effective way to reach the best customers on the planet, it’s complaining to the public that its costs in selling apps or services through the App Store to App Store users is an expense that it must pass on to its customers.

"Rent seeking" and taxation

Imagine shopping in an Apple Store in a local mall and being told that you have to pay a substantial extra fee on top of your regular priced AirPods because the mall charges Apple a lot of rent. Would your reaction be, "yeah, this mall is really out of line charging rent to all of these poor businesses just trying to get by," or would you be mad at Apple for trying to pass off its own business expenses on you?

After all, the reason Apple is renting from that mall is because of its valuable, established foot traffic and accessibility. Apple doesn’t want to develop its own malls or—in most cases—build its own freestanding stores where it incurs new risks far beyond its usual business. So it pays rent and makes less money selling its products in mall stores than it would if you simply bought its products online directly.

Apple doesn't demand free rent from malls where it does business

Yet Spotify considers Apple’s App Store to be something that it is owed access to, and which it should pay nothing for. That’s an opinion shared by some other developers, and even some Apple writers.

Ben Thompson of Stratechery has described Apple’s App Store as "rent seeking," writing that Apple "is leveraging that monopoly [on iOS] into an adjacent market — the digital content market — and rent-seeking. Apple does nothing to increase the value of Netflix shows or Spotify music or Amazon books or any number of digital services from any number of app providers; they simply skim off 30% because they can."

That’s incorrect in a number of ways. First, Apple doesn’t have a "monopoly" on iOS. It owns iOS. Apple’s iOS isn’t an open market that Apple is exercising illegal control over. In contrast, Microsoft licensed Windows to third parties and then restricted how they could do business, such as preventing PC makers from bundling Netscape or QuickTime on their own computers. That was illegal.

But Microsoft owned Office. It didn’t license it out as an open platform and then restrict what people could do with it. To this day, third parties can’t add their own spreadsheet to the Office package and force Microsoft to sell it to their customers as an alternative to Excel, and then take the proceeds and insist that Microsoft simply owes them access to its own customers.

Beyond iOS not being a "monopoly" just because Apple restricts what’s sold in the App Store, Apple is also not "rent-seeking" by asking for a cut from the third party subscriptions it services. That’s a pejorative term that (like Spotify’s "App Store tax" rhetoric) has a real meaning that's being incorrectly stretched into bozo-land. Rent Seeking refers to extracting value from a transaction without contributing to any economic benefit.

The App Store isn’t "rent seeking" when it charges partners a fee to gain access to its extremely valuable installed base of customers because it is actually offering something of tremendous economic value in exchange. Netflix, Spotify, and other subscribers can build their own App Store like Apple did (or as Amazon has), or merely set up their own payment systems and attract valuable clients on their own.

Apple doesn’t have to "add value" to "Netflix shows or Spotify music or Amazon books" in order to charge for access to its store infrastructure, its installed base, or its billing systems. Facebook and Google don’t have to "add value" to your advertising message in order to charge you to advertise it using the digital infrastructure they’ve built.

Apple actually allows third developers to put free apps on the App Store and distribute them without any cost. So if Spotify doesn’t like the costs associated with finding and servicing customers on the App Store, it can build and maintain its own customer base and then send them to the App Store to get a free app they can use to access the subscription they bought from Spotify.

That’s what Netflix is now doing. It’s using Apple’s iOS App Store to benefit from its infrastructure and distribution system and paying nothing for it. Spotify can do the same. But it doesn’t want to because finding new customers is really expensive and difficult.

What Spotify wants to do is to gain full access to the App Store and have no restrictions in sending customers it finds on the App Store to its own system, so it can use Apple without paying for its platform. That’s not a level playing field. It’s asking the government to force Apple to pay the expenses for rival developers.

Spotify also wants to directly contact customers it finds on the App Store so it can sell them services and upgrades without going through Apple. That means emailing them or pushing advertisements on its developer pages that link to its own website. In fact, in 2015 Spotify began sending emails to its subscribers offering to pay them to bypass the App Store when subscribing.

Apple doesn’t allow developer ads or direct emails, the same way that there aren’t any malls that will allow rival stores to put up signs for free designed to woo visitors away to support a store that doesn’t pay rent in the mall. That would be unreasonable to demand from any property developer.

Spotify has also complained that Apple has locked them out of developing integration with Siri, Apple Watch and HomePod. But Apple doesn’t have a responsibility to host competitors and to provide them with the same resources it devotes to its internal services. If Spotify’s services are better—as many subscribers believe—their valuable customers will demand support for Spotify from the hardware Apple builds, and if Apple doesn’t build it, they might go elsewhere. That’s how business works.

The government shouldn’t be giving Spotify privileges to use Apple’s own resources to compete against Apple, for free. Spotify has already proven that it can severely impact Apple’s business; its streaming music operation has crushed the downloads business of iTunes.

Apple was forced to scramble to prop up its position in music with its most expensive ever acquisition of Beats and the expensive deployment of Apple Music—largely because Spotify was eating up its existing downloads business with a new business model that took advantage of radio laws to give users access to music without paying out nearly as much to the rights holders and creators.

That was unfair play, but Spotify doesn’t mention it in its selective set of cartoon depictions of its history in the music business alongside Apple.

Spotify’s hypocrisy in refusing to pay anyone for their work

Spotify’s weepy public play rings particularly hollow because it just fought a decision to pay out increased royalties to songwriters. Apple, unlike Spotify, Google and Pandora, did not challenge the rule, which would require music streamers to pay out more to the talent that created the product they are reselling to customers.

In fact, Apple originally proposed flat streaming royalties, which are fairer to music creators because they would get paid for all the plays of their songs.

Spotify and Google’s YouTube skate around paying full royalties to content creators by offering free streams of music that effectively pay artists very little and devalue music playback as a service. Both services became wildly popular through this cheat. Industry data shows that Apple Music pays out nearly double in royalties to musicians compared to Spotify, while YouTube pays out virtually nothing.

Spotify makes a popular product that works well and is highly regarded. But on both sides of its business, it doesn’t want to pay anyone for the work they’ve done, from the talent that creates music to the builders of the market where it finds its customers.

The world’s leading streamer isn’t some persecuted underdog to be pitied. It’s just another greedy corporation that wants to make money reselling content without paying anyone else in the creation and distribution chain. It doesn’t need a handout from the government to make money at everyone else’s unpaid expense.