Apple's super obvious secret: Services is software

Over the past few years, Apple has increasingly directed analysts' attention to its growing revenues from a segment it calls Services. However, it's common to hear even Apple's happiest of customers frown at the idea, which is often cynically portrayed as an effort by the company to wring even more money from its premium hardware buyers. But the reality is that Services are largely software—and Software Sells Systems.

In 1979, John Couch was in charge of all software at Apple Computer. He commissioned this poster: Software Sells Systems

Apple loves to talk about Services

In yesterday's FQ2 2019 earnings conference call, the word "services" was stated 26 times, compared to just 17 mentions of 'iPhone" and ten of "Mac."

Apple's Chief Executive Tim Cook noted that "it was our best quarter ever for Services, with revenue reaching $11.5 billion," detailing that success was broad based across a variety of things that make up the company's Services segment.

"In fact," Cook added, "we had our best quarter ever for the App Store, Apple Music, Cloud services, and our App Store search ad business, and we set new March quarter revenue records for Apple Care and Apple Pay."

He also stated that "Subscriptions are a powerful driver of our Services business. We reached a new high of over 390 million paid subscriptions at the end of March, an increase of 30 million in the last quarter alone."

Apple's Chief Financial Officer Luca Maestri added that Apple paid subscriptions were "growing in strong double-digits," predicting that "we expect the number of paid subscriptions to pass half a billion in 2020." In other words, next year.

Cook spoke of Services as if they were an entirely new category of thing, stating that "they actually help to eliminate the boundary between hardware, software, and service, creating a singularly exceptional experience for our users."

That's some rather creative wording, but the reality is that the Services Cook was describing are effectively software, valuable applications for the hardware products Apple sells. That's important because it helps to clarify that Services is not really some uncharted new territory for Apple where we're waiting to understand how things might work, but rather a quite well-known subject.

Why Apple likes to talk about Services

The changing climate in Apple's ecosystem

Over its long history as a computer maker, Apple's strategies related to software have shifted dramatically. It was among the first hardware makers to recognize the importance of building relationships with third party developers way back in the late 1970s. It then actually built some of the most critical software shaping the hardware business in the 1980s: the Macintosh platform that was used by developers to build modern, uniform, predictable, intuitive desktop software.

However, in the mid 80s Apple turned around and began to downplay its role as a software maker to avoid contention with its outside developers, a move that—quite counterintuitively—ultimately almost destroyed the company in the 1990s.

It was only in the 2000s—after Apple returned to taking the lead in creating new software for its own platforms—that third parties again began seeing the Mac, iOS and Apple's other new platforms as something worth investing their own resources into.

With Services today, the real question isn't "why is Apple distracting itself in trying to make television, video games, payment systems, news and other practical applications of the hardware it builds," but rather: "why hasn't Apple already invested even more into making its hardware inherently and uniquely valuable to users?"

There was nothing to handle in the "hands on area" of the Steve Jobs Theater

Apple's Services Event flew over many heads

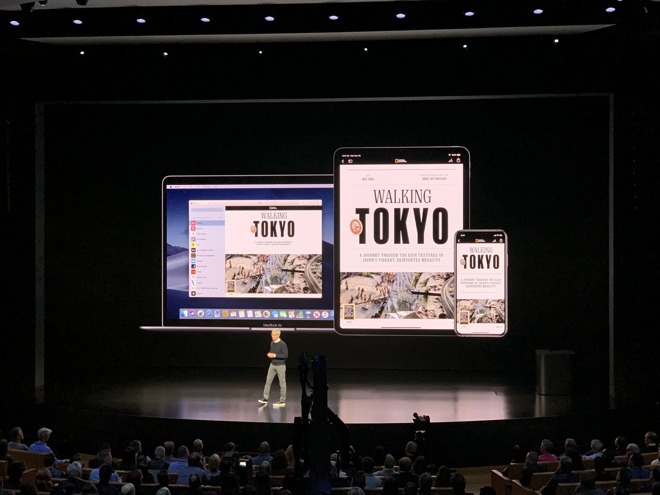

When Apple invited the media to its March event this year, it was clear from the start it would be focusing on a variety of new subscription services rather than any new hardware. After all, it updated its iPads and iMacs and released new AirPods in the week prior to the event just using Twitter and a few press releases. Apple's events exist to drum up excitement for new product releases, but nobody needed to be walked through why faster iMacs or updated iPads were necessary. Did they need that for these new Services?

Apple reserved the entire event to talk about its new Services, leaving the "hands on area" of the Steve Jobs Theater completely unused for anything but attendee selfies (above). This was perhaps the first time Apple had ever devoted so much attention to Services since Steve Jobs presented—in his final keynote at WWDC 2011—that Apple's new iCloud services were as monumentally important to the company as a strategy as macOS and iOS were. The three were literally given equal standing in WWDC banners and Jobs chose to present iCloud himself, while delegating the other two keynote subjects to his team.

My experience at that event, as well as this year's March event, reminded me a lot of Jobs' 2010 presentation of the first iPad: he clearly articulated how things were going to develop into the future, yet many if not most in attendance couldn't grasp what was being outlined. An overwhelming number of the hot takes scribbled up afterward largely sounded like pretentious clowns desperately trying to appear relevant by insisting that Apple had really jumped the shark this time and was just wasting our time without really offering anything new or compelling.

This year, you could almost feel the audience demanding to know, with crossed arms, "yeah but where's the thick new MacBook keyboard that can eat a bagel and still never miss a keystroke? And where's Apple's response to the Galaxy Fold? And when will Apple ship a 5G iPhone that is as urgently, critically needed right now as WiFi 7 and Bluetooth 6?" The media is sick of being Apple's lapdog, but can't get enough of serving that role for Microsoft, Samsung, and Qualcomm.

The tech media's overwhelming inability to "get" iPad, or iCloud, or today's Services feels like willful ignorance dressed up as condescension from people who think they know what Apple should be doing. Yet clearly they haven't manage to successfully pick up what Apple's been putting down for a decade now, while carrying water for rivals that have actually been repeatedly wrong over the same period. That also applies to Apple's Services.

Apple's new Services of software is not just a Netflix

Apple's big push into new Services are often equated with Netflix. And often, Apple is portrayed as making a desperate stab at catching up to the perceived leader in subscription television content. That's not really accurate though.

Netflix has many fans. That includes me; I've subscribed to Netflix since its mailed-in DVD days. But Netflix as a business is a high cost, high risk enterprise that doesn't actually make very much money. And Netflix largely exists to sell subscription access to the original content it produces. It doesn't really have a hardware business and increasingly is less about other studio's movies and more about its own in-house content, some of which is really great and might never have been produced elsewhere if Netflix wasn't funding its development.

Apple is developing new Services—including Apple TV+— to similarly earn ongoing subscription revenue. But it's pretty clear that Apple TV+ is less like Netflix and more like iTunes: a business that's designed not just to sell access to content, but to produce original content that is tightly linked to Apple's platforms in a way that helps to sell Apple hardware.

Like iTunes, Apple could earn nothing from Apple TV+ and still be creating content that helps sell its sustainably profitable hardware. In fact, iTunes was operated as a revenue neutral enterprise for some time before Apple couldn't help but make money from it. The point of iTunes was initially to make sure commercial music and later TV and movies were available for Macs and iPods. If Apple had left that up to Microsoft or Sony, it risked having those outside players yank their content from Apple's platforms, or dictate what form of DRM Apple would have to support.

iTunes slowly grew into a viable music business of its own. But the iTunes Store really got valuable once Apple expanded its content sales into iPod Games and then iPhone Apps, which contributed a larger profit margin to Apple as a store keeper, and also created a universally unique new category of content that only benefitted Apple. When Apple sold a U2 album, Mac and iPod users could play the same songs that Windows PC users could buy elsewhere. But when developers created titles like Angry Birds for iOS, it was content that Symbian, Palm, and Windows Mobile phones couldn't use unless the developer decided to also invest in porting the same content to their other platforms.

Apple's hardware-free March presentation was actually all about its hardware

So while iTunes kept Macs and iPods relevant in a world dominated by Windows and enabled users the option to choose Apple's hardware, the App Store helped to make iOS dominate in mobile devices, and actively drove sales of iPhones and iPads while making it harder to chose a device running a fringe platform like webOS, WP7, or Tizen. And even with huge volumes of Android sales globally, Apple continues to maintain a lock on software app sales that set iOS apart. Hit games arrive on iOS first. Even Microsoft brought its Office apps to iPad first, despite pundits shouting that Android was leading market share in tablet sales.

A significant chunk of Apple's existing Services are subscription apps. Apple also throws in some licensing revenue, the company's income from its agreement to keep Google integrated into its Safari search, and some other non-hardware revenue such as Apple Care.

But overall, all of its new Services and most of its existing Services business are purely software—useful applications of hardware that help drive hardware purchases in addition to generating revenue on their own. Take a look at what these new services mean for Apple, starting with tomorrow segment on Apple Arcade.