SOUL OF A NEW MAC: MOJAVE PUBLIC BETA

Apple’s macOS Mojave is still a work in progress, but the strategy is clear: Welcome to the Mac for iOS users. And Don’t Panic!

Three weeks after Apple's software chief Craig Federighi first showed off macOS 10.14 Mojave at the company's Worldwide Developer Conference in the first week of June, Apple has released the first Public Beta of its revamped desktop operating system.

Mojave features a Dark Mode, Stacks for organizing the Desktop, a Finder Gallery view with full metadata and common editing tools, Markup in Quick Look views, new apps including News, and lots of other iOS-familiar features.

The Mojave release offers a clear look inside Apple’s strategic thinking and the state of the art in 2018—both in what it aspires to deliver and what it doesn’t even make an attempt to do.

There are no ads on the desktop, for example, and Siri isn’t always listening to determine what TV shows you’re watching the background so it can most effectively sell your data to advertisers.

The engineering decisions made for the Mac—alongside iOS 12—will shape the future of technology across the next year for the world’s largest and most successful vendor of premium personal computing and mobile enterprise hardware.

Apple is crafting an integrated hardware and software experience that sells you the product, rather than selling "you, the product," and the result is a rarified, luxurious experience.

If you already own a modern Mac, the Mojave release is Apple’s latest annual gift, designed to significantly upgrade your overall experience in several major ways and across a broad array of minor thoughtful touches, adjustments and fixes.

If you don’t own a Mac, Mojave will make you want one.

What’s new in macOS Mojave

While reviewing the Public Beta in advance, it repeatedly occured to me that the overall intent of this release is to make the Mac the ideal computing system for iOS users. As I run through the new features, you’ll see what I mean.

The most obvious new feature is Dark Mode, which not only shifts the appearance of entire user interface, but also focuses your attention on the task at hand and your own content, much the same way iOS was designed to do.

Mojave's new Dark Mode for Macs has no direct equivalent on iOS, but it serves the same attention-focusing purpose as the mobile-optimized user interface of iOS.

Similarly, the new Mojave Desktop features Stacks, which offers to organize your messy screen of document and app icons in a way that makes sense to you: by type, dates, or label. It feels a lot like the purposely unmessy iOS Home screen.

Mojave’s new Screenshot behavior is taken directly from iOS, enabling you to "grab" a screenshot image, edit the capture via Quick Look and immediately use it (rather than just dropping it somewhere into the PC file system).

This screen shot—of a screen shot—depicts the iOS-like behavior Mojave presents. Click on the lower right image before it disappears, and you're taken into a Quick Look where you can edit or share it.

New Quick Look editing features also feel iOS-familiar, allowing you to mark up images, sign a PDF, and trim videos without having to even launch an app.

Mojave also delivers new Mac versions of iOS apps for News, Stocks, Voice Memos, and Home, and now integrates FaceTime right into Messages. Mojave also borrows from last year's App Store overhaul on iOS to deliver a new Mac App Store that feels more like a curated catalog of developer artwork than just a software repository.

You don't need to worry that Apple is merely dumbing down the Mac to make it a large format iOS platform. As the design of the new Mac App Store highlights, Apple is increasing the familiarity of concepts between its platforms while retaining the differentiated nature, advantages, and character of its desktop computing platform.

The Mac version of the App Store doesn't just showcase tabs from iOS for Apps and Games, but calls high-level attention to sections for Mac software used to Create content, Work on projects and Develop code.

The new Mac App Store in Mojave benefits from Apple's previous work on iOS but isn't just a simple port.

Mojave also applies iOS-like controls for security and privacy, forcing Mac apps to ask your permission before they access your personal data (including contacts, calendar, reminders, photos and your location), and before they can activate the camera or microphone.

There are also new controls for limiting how advertising can track you, including tools that block "fingerprinting" and other techniques advertisers use to personally identify you and pair this with your browsing behavior on the web.

Mojave also makes it iOS-easy to suggest secure passwords for accounts and websites, and even recommends changing passwords that you use too often. That’s super smart in our new world where Yahoo or Twitter getting hacked might mean somebody has also gained access to every other site where you used that same password.

Siri now knows how to look up a password in your Keychain ("what’s my Netflix password?"), and with the new Home app, you can now manage your entire HomeKit setup on your Mac. There are also a series of other new Siri features, including the ability to "find my iPhone" (or AirPods).

Siri gains the ability to do some useful new things that actually make sense to request from your Mac, such as invoking iCloud's Find My iPhone or AirPods.

There are also other tight new integrations between iOS and Macs, including the new wireless Continuity Camera that turns your phone into an untethered imaging device and document scanner for your Mac.

Macs have always been the way to build iOS apps, and Apple is enhancing that with new Xcode 10 tools for developers. That includes powerful Machine Learning resources for app developers, which now support faster model training. With the new CreateML, developers can even build and train new ML models on a Mac (this previously required a dedicated server).

And of course, Apple is also positioning the Mac as the way to design and build animated 3D objects in the new USDZ file format for use in Augmented Reality with iOS 12's new ARKit 2.0, which will roll out in parallel this fall.

The ARKit apps and animated 3D models they use are built for iOS by Macs.

This is all just a quick overview of the new Mojave features, so I hope you still have free time to follow me along as we dive deeper into what Apple’s doing and why. But first, let’s take a look at what Macs Mojave will work on, and what you should consider before trying out the Public Beta yourself.

Mojave requires Metal

Macs supporting the new macOS Mojave are identical to Apple's list of Mac computers that support Metal.

Mojave will require at least a Late 2012 iMac or Mac mini, or a Mid 2012 MacBook Air or MacBook Pro. It also of course runs on any new 2017 iMac Pro or new Retina MacBooks (released in 2015), and supports all of the black cylinder Mac Pros (released since 2013). It also supports the earlier "cheese grater" Mac Pro models back to Mid 2010, if equipped with a Metal-capable graphics card.

Mojave requires a Metal-capable GPU

Lack of support for Metal graphics is why some of the Macs that are supported in today’s macOS High Sierra can’t be upgraded to run Mojave. This includes 2009-2011 ("non slim") iMacs; 2010-2011 Mac minis; 2009-2010 plastic non-Retina MacBooks; and 2011 or earlier non-Retina MacBook Pro and MacBook Air models.

The new Mojave drops support for a couple years of non-Retina models, but still supports some non-Retina Macs, as the problem isn’t their display resolution but rather their GPU capabilities. Older Mac Pro models dating back to 2010 can be outfitted with new Metal-capable GPUs to run the new release, making it clear Apple isn't just dropping legacy machines to force new purchases.

Drawing a line at Metal-capable GPUs allows Apple to optimize graphics performance—particularly for entirely new software features including multi-user FaceTime and other new iOS-familiar UI features. If you’ve owned a Mac for 8-9 years, Mojave offers a good reason to upgrade your hardware and join the modern Metal party.

The new Mojave release will officially ship this fall alongside a new iOS 12, watchOS 5 and the new tvOS, following what has been Apple’s regular schedule for OS updates for several years now. In advance of this, Apple is offering a Public Beta program where users can opt in to download prerelease software, test out its new features in advance and report any bugs they discover to Apple.

And now: a warning!

Note that most users should not download a Public Beta! This is especially the case for anyone who would have their life or work inconvenienced by having to track down complex problems, potentially including hardware that won’t boot or a full restore from a backup. That in itself can take hours to perform, particularly in our modern age where you likely have 100 GB or more of photos alone.

It’s not just that the Mojave Public Beta could have some wild bugs hiding in there as it develops—in our modern age of cloud-connected everything, even a minor bug could trigger a chain of events that might end up corrupting your Keychain passwords, duplicating contact records, borking your HomeKit configuration, or erasing pictures you expect to be synced to iCloud.

Let me emphasize this one more time: you don’t just need a solid backup before you install a Public Beta; you need the flexibility of hours of free time to sort out any problems that might result from using early beta software!

Apple calls is beta releases "pre-release versions" for good reason!

Ideally, to run the Public Beta you should have an extra Mac with a separate copy of your data, so if things go sideways you can erase it and start over fresh. Keep in mind that if you connect a Public Beta machine to your iCloud account you could end up tainting all sorts of your online data that could be complex to straighten out later.

I personally have been using Public Betas (and Developer Betas) for decades, from before even the very first Rhapsody release in 1997. I’ve certainly survived, but I still have weird bugs that follow me around, from corrupted contacts to fantom photos in iCloud and probably corrupted application preferences that lurk in the background, waiting for the next Beta to implode into crazy behavior. But that’s kind of my job.

Tread cautiously, and don’t blame the beta for being beta—you’ve been warned!

Now, if you’re the Think Different type who loves solving challenges and playing on the bleeding edge of technology, Mojave Public Beta will be right up your alley. Apple is releasing this just for you. Enjoy. And report the bugs you run into so Apple can fix them for everyone else who can’t be a beta hero.

To install the Public Beta, you just sign up on Apple’s site and it delivers a certificate that’s installed for you that allows you to download prerelease OS versions. It should automatically download new Public Betas as they are issued, typically about every month or so until the official launch around September. Once the final release ships, you can upgrade to that with everyone else.

Dark Mode is the new Aqua for modern Space Grey Macs

While the new software update supports a long tail of older Macs (dating back as far as 2010) it’s particularly a treat when used on new machines, especially the recent generations of Retina Display MacBook Pro, and, I assume, the dark racehorse that is the iMac Pro (which I didn’t have available for testing).

These premium, luxury class Macs were clearly built in anticipation of the Mojave release, with its new Dark Mode user interface that echoes Space Grey metal and the black display bezel the same way that the early 2000’s Aqua UI of the first editions of Mac OS X reflected the translucent plastics of the Macs of that era.

The original Mac OS X 10.0 reflected the translucent plastics of early 2000's Macs.

The Dark Mode of Mojave is the natural progression of Apple’s work over the last few years that introduced developers to dark UI concepts—and the work that would be required to get their apps ready for a system-wide Dark Mode in the future. It might sound simple, but the work needed to make existing apps consistently look great in Dark Mode was a complex process that involved years of efforts. Third party developers are still working on it. Even Apple's own iWork team is still working on it.

The first modern suggestion of an alternative system wide Mac UI that I recall was presented at WWDC 2015—among guidelines for developers on how to make sure their apps followed best practices in design. Since macOS Yosemite (2014), Apple has been offering the option to display a "dark menu bar and dock," baby steps toward Dark Mode.

Even earlier, Apple had been experimenting with ways to highlight and focus attention using a minimal, dark UI. Back in the late 90s, Apple experimented with Brushed Metal as a way to distinguish QuickTime, then after acquiring Final Cut Pro, kept its dark grey interface as a way to focus attention on video content. Logic Pro, acquired in 2002, also featured a dark UI, which Apple retained and used across other Pro Apps.

Apple's Logic Pro X has a content-focused UI for professionals—carried over to Logic Remote on iPad.

In 2005, Apple’s new “Front Row” UI for Macs focused attention on playing movies, music, photos and podcasts. The concept of dark framing progressed with full screen iLife apps and then system wide support for third party Full Screen Apps in 2011’s macOS Lion, where a single app not only took over the desktop, but typically used a minimal, dark UI to focus attention on what the user was doing—as Apple’s own apps (including iPhoto) had previously explored.

Dark Mode on Mojave blends the display into your MacBook Pro’s backlit keyboard and—surprise!—the Touch Bar.

Touch Bar is already Dark Mode.

If you have a MacBook Pro with Touch Bar, this release is for you. It looks like the screen melts into the keyboard with the kind of precision that Steve Jobs would unleash upon the world, developed out in the open as if in slow motion—but none of us anticipated it until it dropped. It’s like we thought it was a finger bowl but it was really Palmolive and we were soaking in it, as Madge had to point out.

Actually, it wasn’t wholly unanticipated that with OLED coming, Apple would make a dark UI a cool new fashionable look—a vast swing from the original bright, light OS X interface with its hyperrealistic icons and glossy translucent effects.

Back in the early 2000s, Jobs was showing off the power of OpenGL and GPUs to do unprecedented Quartz Compositor effects with translucency and texture mapping for Aqua—it effectively turned the desktop into a video game, a solid five years ahead of Microsoft being able to copy it.

Right now Apple is focused not just on the engine doing the drawing, but on the display—working to fully exploit the super efficient, hyper contrast, ultra vivid nature of OLED technology (and microLED after it). Macs are still shipping with LCD screens, but OLED is coming and Dark Mode will be ready for it.

The best way to show off the OLED future today is with a dark UI. As Microsoft fans like to point out, that company tried doing this long ago with its early generation OLED-based Zune with a mostly-black screen. It was so dark Microsoft launched the product in a candle lit room, hoping journalists wouldn’t notice that the screen wasn’t actually very bright (they didn’t).

Apple Watch similarly launched with a dark UI because it has both a small battery and an OLED screen that needed to be bright. Touch Bar (which is also implemented using an OLED panel) is itself super Dark Mode already.

Mojave's Dark Mode makes Touch Bar really pop, especially in the dark.

When you use Mojave Dark Mode, it makes the Touch Bar really pop as an extension of both the keyboard and the display. It’s not an accident that all of these technologies emerged together at Apple this year.

How do you take your Cocoa?

You might not like Dark Mode. It can be great for working in low light, and has a cool, futuristic feel to it. But the alternative “Light Mode” feels right (or at least more familiar) when I’m working. When you’re working in Light Mode, Touch Bar feels like it becomes detached as part of the keyboard.

Light Mode is a “good morning,” drink coffee, edit a presentation, get shit done sort of thing. Dark Mode is a kick back watch an online movie, smoke a bowl, edit photos, type up some good ideas kind of experience. It’s smart to offer both, and that’s what Apple is doing.

You can swap between the desktop examples below to see how Light and Dark Modes emphasize different elements. (Also visible below: now there are favicons in Safari tabs, and when you select multiple documents in the Finder, they pile up in a spiraling stack).

The new Dark Mode is not a forced transition in the model of Microsoft’s 2007 Windows Vista "Aero UI," or the even worse "Metro UI" it shipped on Windows Phone in 2010 and then foisted upon many unappreciative Windows 8 users in 2014. The new Dark Mode of Mojave is a choice. That’s also distinct from Apple’s own forced transition of the "Clarity, Deference and Depth" UI released in iOS 7 (which users scrambled to download).

Apps (like Mail, above) can offer to present light backgrounds in active windows while in Dark Mode. (There's also now a toolbar button in Mail that presents Emoji characters).

Some apps let you strike a middle ground. For example, Apple’s Mail (above) and Notes both have an option to give their working documents a light background while the rest of the system remains in Dark Mode. This combination really makes your active window stand out as a focus of attention while everything else fades into the background. It’s currently my favorite way to work.

But of course, you can change the UI Mode anytime with the click of a box. It takes less than a second to redraw the screen in your new choice. You can also select a Highlight Color (used in text selection or menu bars) and one of eight Accent Colors (used in UI elements like Checkboxes and Radio Buttons, similar the "Blue or Graphite" Appearance option in High Sierra).

Light and Dark Appearance settings in System Preferences

The 30 bit Dark Mode

Mojave’s Dark Mode appears a bit reminiscent of NeXT’s advanced desktop operating system that Jobs built in the late 80s after leaving Apple, and what he brought back to the company when he returned in 1997—effectively turning Apple around and saving it from collapse.

The original NeXT desktop was naturally dark because it used just four shades of grey (2 bit color) to maximize its graphics computing power, skipping support for chrominance entirely to radically push the state of the art ahead in sharp megapixel resolution rather than color depth.

NeXTSTEP launched with a dark UI 30 years ago.

The original Mac did something similar with its 1 bit color: it could only produce black and white pixels, using patterns to approximate shades of grey. But focusing its resources on high quality display technology rather than color allowed it to deliver accurate, sharp square pixels in an era where most PCs were drawing text using blurry rectangles with 16 ugly colors.

Color depth is no longer a scarce resource. Starting with last year’s 15 inch MacBook Pro, Apple now has modern production Macs with support for 30 bit color—more than 1 billion colors (10 bits per RGB channel). Any yet rather than making the desktop an egregious rainbow of unrestraint, Apple is releasing Mojave with a subdued, Dark Mode that makes very subtle, meaningful use of color.

That’s also what the company did when it debuted Touch Bar, which is designed to primarily stay black and white unless color adds some useful function or information. Light UI is similarly tame in its use of color. This all has the effect of focusing attention on your own documents, particularly when editing vibrant photos or HDR video.

Beyond its integration into Dark Mode, the new Mojave gives the Touch Bar some additional attention. You can create custom Automator actions and install them into the Touch Bar's Control Strip for easy access. And when a website sends you a security code via SMS, it will also pop up in the Touch Bar to tap rather than having to type it in, just like the QuickType keyboard in iOS. Touch Bar is effectively a Mac-sized QuickType panel.

Continuity comes to the camera

Next to making the Mac as task-focused as iOS, there’s also another thing Apple has been increasingly doing on the road to Mojave: breaking the legacy that ties modern users to the most complex, problematic and difficult elements of the desktop computer, starting with its file system.

Apple has been pushing iCloud for years now as a way to store files without thinking about hierarchical file system paths. AirDrop has similarly worked since 2011 as a way to move documents across the network without configuring file system shares.

Since 2014, Apple’s other wireless Continuity features have increasingly integrated iOS devices with Macs, including Handoff for moving documents between systems, Auto Unlock, the Universal Clipboard, Instant Hotspot, bridged calls and SMS.

Mojave now includes Continuity Camera, a feature which replaces the Mac “webcam” with wireless connectivity to the much better camera you carry on your iPhone. The concept lets your Mac request a photo or document scan from your mobile device. You take the image and it is immediately sent and embedded right into the document where you need it.

In the future, expect macOS to tap into using the 3D TrueDepth camera of iPhone X (and better) devices to deliver real-time object modeling on your Mac. You could even use point cloud imaging or the live depth videos that TrueDepth can capture—even in the dark.

But right now, macOS Mojave aims at delivering exactly what people have a real need for doing from a desktop: using their iPhone to snap a photo, scan a receipt, letter or other document. All effortlessly—to add images to a document without dealing with sync or emailing or consciously thinking about how to beam a photo to your PC.

This functionality wasn’t constantly working for me in the initial Public Beta, although when it did work it was super slick. From within any document, you can right click to bring up a menu that includes your discovered iOS device, with options to Take Photo or Scan Document. Select photo and your phone goes into camera mode to take a picture. You can then retake or approve it, and as soon as you do it inserts your photo into the document.

Scanning a document works similarly, using the Document Scan feature Apple added to Notes last year. You point your camera at a document and it defines the edges and corrects for alignment, making it super easy to import a high quality image of a letter, receipt, copy of your ID or anything else. You can manually correct the edges, and as soon as you approve on your phone, it’s inserted into the document. It’s a really nice experience.

This sort of feature is not exactly rocket science to deliver. It is, however, functionality that will be far easier for Apple to perfect between its limited range of Macs and its modern iOS devices, compared to the task of any PC or Android device maker who would like to roll out something similar.

Apple has a smaller PC base than all of Windows, and a smaller mobile base than all of Android. But it has a vastly larger group of users who can directly benefit from Continuity features that provide effortless, genius simplicity in moving tasks, images, keychain passwords, contacts and everything else between the mobile iOS world and its high end PC experience on the Mac.

Imagine the work required by Google or Microsoft to get their licensees to adopt a single new camera sharing protocol and then not introduce their own proprietary version instead. Now estimate how many years it would take for a new version of Android or Windows to trickle out into the user base. Meanwhile, Apple can make it “just work” extremely well within a few months.

The Mac Desktop: Dynamic Desktop & Stacks

Apple has previously made efforts to harmonize iOS and the Mac desktop related to how they use touch gestures to multitask between apps. It also brought the iOS Home screen to the Mac in the form of "Launchpad," something I find too simplistic to be very useful.

Fortunately, Mojave makes it clear that Apple isn't just trying to water down the Mac into a larger, more expensive version of iOS. There are some unique (albeit familiar feeling) new features the Mac gets that are specifically aimed to take advantage of its orientation as a desktop of document windows.

Complementing Dark Mode on the desktop, Apple has introduced Dynamic Desktop pictures, a set of morning, day, evening and night images that shift throughout the day to reflect the passing of time.

Dynamic Desktop pictures change throughout the day, reflecting your local time.

The Public Beta includes one of these: a sand dune from the Mojave Desert. Expect a series of these to roll out like Apple TV's aerial screensavers. There are also static Day and Night versions of the Mojave scene if you prefer.

In a more functional direction, Apple has also enhanced the desktop to offer Stacks, dynamic folder-like piles that can sort your desktop items by Kind, a Tag label you have assigned, or by the Date they were created, last modified, last opened, or added to the desktop.

You can start using Stacks to organize your mess of desktop files by date, project or kind, then turn Stacks off to return to how things were.

It's hard to believe that it was over ten years ago (2007) that Steve Jobs first presented Stacks in the Dock as a way to easily access items in folders like Documents and Downloads.

Stacks on the Desktop work somewhat similarly: click one and it opens up, scattering its contents across the desktop. Click on it again and it all collapses into a single item.

Stacks are a little bit odd in a few ways however. First, they only exist on the Desktop. Open a Finder window and there's no representation of Stacks inside the Desktop folder.

Also, Stacks organize themselves differently than the Finder does. If you sort them by Kind, regular Images are separated from Screenshots (which are sorted out by metadata, not just by having "screen shot" in their name). That's handy, but different from how Finder windows sort by Kind. This inconsistency will hopefully be addressed in beta.

Another oddity is that when you open a Desktop Stack, rather than working like a Dock Stack (or an iOS "Folder") to present a panel of items, it deals out all of its items as icons on the Desktop (a behavior I prefer), but it also pushes down all of the other icons, including other Stacks. When you open and close different Stacks, you end up with file icons arranged in a sort of Windows-like mess; sorted but unpredictably.

However, you can also activate Stacks to work with your Desktop files sorted into groups, then turn Stacks off to return to your familiar spacial layout of items returned right back where you had placed them on the Desktop. This makes Stacks a great way to isolate a specific set of items by date, project or kind without losing your messy style of personal organization.

This makes Stacks very different than the "Sort by" Grid or "Clean up" options (which are still there). Stacks is a new sort of "lossless" organization, a throwback to the Spacial Finder, where things were always where you left them because the system cares to remember.

Finder & Quick Look enhancements

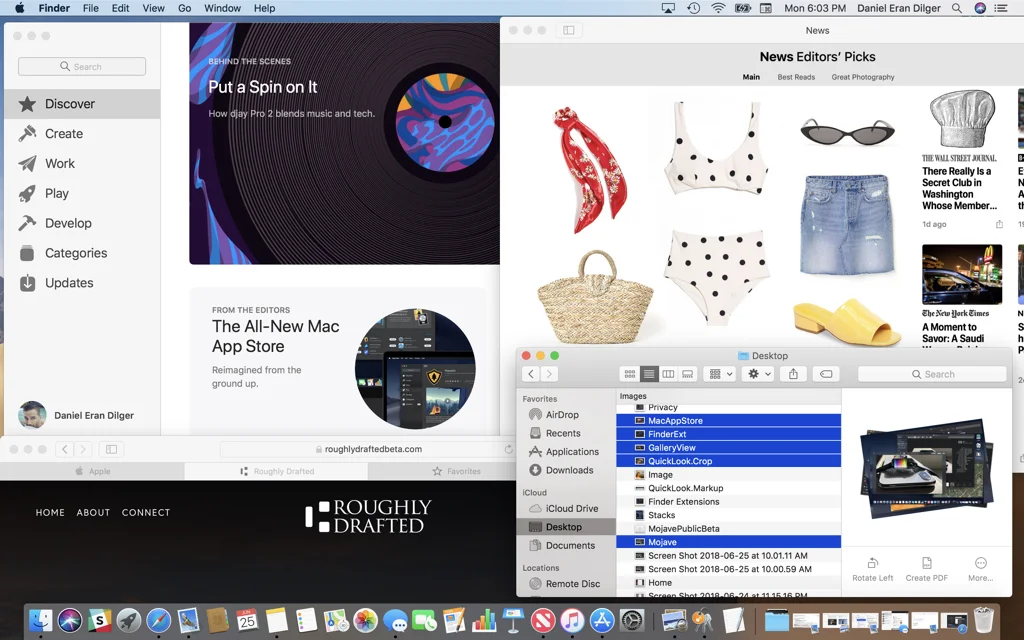

While Stacks offer to organize the Mojave Desktop, the new Finder offers new view of your other folders: called Gallery, it replaces Cover Flow (which looked cool, but you probably never actually used it).

In Gallery view (below), you get a large preview of a single document, with a scrolling series of its neighbors below it. It's sort of like Cover Flow with a Quick Look above it. Additionally, next to the featured document in the Gallery you also get a Preview panel. However, in Mojave, the Preview is now devoted to the document's detailed metadata, rather than just showing a large thumbnail with some limited file information.

The Finder's enhanced Preview pane in Gallery view presents more technical metadata, and Quick Action buttons.

Preview is perfectly suited to the Gallery view, but you can also turn it on in other Finder views: the standard Icons, List or Column view. It effectively presents a full panel of the metadata you'd see in a Get Info panel, dynamically presented for each file you click on.

For images, Preview can show even more details than a Get Info panel, including aperture and ISO. It shows virtually everything but the URL associated with downloads and the geolocation of photos (both of which Get Info shows. It would be cool to have Preview load a map for a photograph's tagged location, or at least a link to the Maps app).

Along with this technical file metadata (which it seems Apple has always sought to hide from users), the enhanced Preview pane also sports contextual Quick Action buttons: by default you can Trim an audio or video file and rotate or Markup an image, or turn it into a PDF. There's also room for your own Finder Extensions, which you can load and install in the Extensions pane of System Preferences. You can even create and load your own Automator actions, for performing routine actions on files within the Finder.

You can now add Automator Actions to the Finder's Preview Panel, the Touch Bar or the Services menu.

Apple supplies some basic Quick Actions you can manually enable for basic transcoding of audio or video files or using the selected image as your desktop photo.

It appears that with iOS serving up a simplified UI, Apple has relaxed its aversion to exposing more powerful features on the Mac. And yet this new functionality is not overwhelming and doesn't slow down the system. It just feels like macOS Pro.

The Finder's supplied Quick Action buttons are effectively the same tools presented when you Quick Look a document. When you hit the spacebar to Quick Look, you get a larger preview in its own window, with buttons at the top to Trim media files or Rotate or Markup an image. Quick Action Finder buttons jump right into a Quick Look editing mode.

For images, that makes Quick Look nearly the same as opening the file in Preview (which you can also do from Quick Look). However, you can have multiple Preview documents open at once, while Quick Look only opens the currently selected document (the difference is hinted at by Quick Look's more translucent window effect).

The odd thing about Quick Look and Preview is that each presents a Markup mode with a slightly different set of tools in a different arrangement. The two window bars below portray the same image opened in Quick Look and in Preview with Markup.

A Quick Look panel and Preview window of the same image present slightly different Markup tools.

Both have identical drawing, shape, text, signature, lines, color and font selection tools. But Preview presents selection tools (rectangular, elliptical, lasso, smart lasso and Instant Alpha); a color adjustment panel (similar to Photos) and an image resizing panel.

In Preview, the selection tool is on by default, so you can create a rectangle and crop. In Quick Look's version of Markup, the drawing tool is on by default. To crop, you have to click on the crop icon, which presents a different style of selection box (below). It's not clear why these are inconsistent. Hopefully Apple will fix Markup so that it works the same everywhere. Quick Look's cropping style feels more like iOS.

Cropping an image using Markup is oddly different in Preview and Quick Look.

iOS apps coming to Macs

Also note that in Mojave, Apple has taken the first steps to solving a major Mac issue: the Mac user base is not as large as iOS or Windows or Android. It can be riskier for developers to invest in Mac software titles. The Mac App Store has been a lot less exciting than the iOS edition. That’s the case both for users and for developers trying to support themselves.

In Mojave, Apple has launched an internal program to bring some of its own mobile apps built using UIKit (the development framework of iOS) to the Mac. The first apps to take advantage of this are News, Stocks, Voice Memos and Home. On Mojave, they look and feel like Mac apps (for the most part).

News brings Apple’s internal newsroom-curated headlines to the Mac, and cloud-syncs your channel and topic preferences, saved articles and subscriptions with iOS. Stocks does the same thing, tying in the same Apple-curated market news and tickers you use in iOS 12 (both are greatly enhanced over the existing Stocks app on iOS).

Mojave's News app is built using UIKit, but looks and works like other Mac titles. You can dismiss the sidebar to focus on a single, uncluttered view of an article.

Voice Memos lets you record (in AAC or lossless), trim, and edit audio clips and sync these across your devices, making it similar to Notes for audio clips. In the Public Beta, it seemed to be the least finished of the four UIKit-based apps, and wasn't working well enough to really test out. I also wasn't able to sync recordings captured from iOS.

Once it's finished however, it's designed to both record clips locally and to play back recordings you capture on your iPhone so you can take notes or incorporate audio clips into other documents on your Mac. You could also record mobile audio on iOS for use in songs or podcasts in GarageBand or other apps on your Mac.

One new feature of Voice Memos is the ability to name your recordings by default with the location where you captured them, which is a handy way to identify clips without having to listen to them.

Voice Memos isn't yet fully functional but promises to bring your iOS recordings to the Mac (and vice versa).

Similarly, Mojave's new Home app brings your HomeKit configuration to macOS, enabling you to securely control all of your devices on your Mac, as well as share access to family members and guests. You can also get Home-related notifications for door cameras and other devices, and control your HomeKit devices remotely from your Mac while traveling (after setting up an Apple TV or a HomePod as a local hub at home).

The new Home app looks just like Apple's iOS version. In fact, it still has some of the iOS-specific trappings of its UIKit cousin. The setup for a new Scene (below) not only sports a very multitouch page-oriented interface, but the label tells you to "press and hold" to configure accessories. On a Mac, you actually double click on the icon to configure it.

Like Voice Memos, Home is definitely still a work in progress. But as with Apple's other UIKit apps being included in Mojave, it shows the potential for iOS-only apps to transition to the Mac with less work for developers while offering a far better experience for users than simply being offered a web app interface.

Mojave's Home app is still stuck firmly in iOS land, but shows off the potential for UIKit apps on Macs.

Siri on a Mojave Mac can also now be used to control all of your HomeKit devices, whether the Home app is launched or not. You can lock doors, turn on lights, check the status of your garage door, orchestrate scenes and set up automations that perform actions at specific times, when you enter a given location, or when a motion sensor is triggered.

Next year, Apple plans to make its Mac UIKit frameworks (enhanced over months of deployed experience) available to other iOS developers, making it possible to bring thousands of apps from iOS into the native world of Macs, where they will work just like native Mac apps written to its AppKit frameworks.

This will make it that much easier for iOS owners to buy a Mac, knowing that the apps and games they use will likely be delivered as cross platform titles. In addition, Apple is also years-deep into making it effortless to sync data, documents and other content between its iOS and Mac platforms via iCloud, Continuity and related technologies.

On top of all of this, Apple is also launching a new Mac App Store with a layout familiar to iOS users, featuring a set of highlighted titles under its Discover tab, along with four featured sections of desktop Mac apps: Create tools, Work productivity, Play games and Develop tools. There are also 21 other sorted categories of Mac Apps to browse.

The new Mac App Store makes it easy to find new titles by type and by specific category.

The new Mac App Store continues to be where you can individually update your apps, but Apple has moved system-level updates to Software Update in System Preferences. That’s actually a move back, but makes more sense. It always felt weird to go to the Mac App Store to look for OS updates.

The change also brings macOS into line with iOS, which also delivers its system Software Updates in Settings/General, not through the iOS App Store.

Software Update's Advanced... button (below) supplies options to automatically check for updates; download new updates; install updates to macOS; install App Store updates; and to install system data files and security updates.

Have I convinced you yet that Mojave is aiming the Mac at Apple’s own iOS users who want to be creators?

Around the launch of the original iMac back in 1998, Jobs enthralled an audience of developers by noting that there was an installed base of 22 million Mac users. Today, there are well more than five times that number, but more importantly there is an installed base of more than 500 million active iOS users.

Mojave Internationale

Apple has proven that there is exceptional demand for its premium priced iPhone X around the world, even in territories where pundits insisted that nobody would pay a premium for a high-end device. It's also selling millions of new iPads to first time buyers.

Apple isn't just planning to sell these new iOS buyers apps, music, subscriptions and other Services. Many of these users will also want a Mac to (among other things) address the demand for creating apps and other content that the vast, premium installed base of iOS is inducing.

That helps explain why Apple is devoting significant new resources specific to Mojave into supporting languages, features and subjects of interest in regions where iPhone and iPad are selling, including as China and India.

Mojave supports new system languages including English variants for the UK and Australia, French for Canada, and also Traditional Chinese specific to Hong Kong. And for all speakers of Traditional Chinese, Apple has enhanced the translation of names for apps and features (including Boot Camp, News, Mission Control, Launchpad, and Mail Drop) to make them easier to understand.

Siri Dictation in Simplified Chinese also now automatically inserts punctuation. And Siri can also now understand questions about Chinese holidays.

Apple also now supplies its "Word of the Day" screen saver for Simplified Chinese and Traditional Chinese.

Chinese restaurant names have been added to the language model for Simplified Chinese, making them easier to type. And Maps now recommends popular dishes for restaurants in China.

Apple is expanding and enhancing Siri support globally, improving dictation and areas of knowledge in strategic markets as Macs follow iPhone sales.

For Japan, Mojave now supports improved keyboard input, enabling users to type English and Roman alphabet words via romanization, typing words phonetically. Mojave recognizes the intent and provides correct English spellings.

Mojave also now includes new dictionaries for Hebrew, Traditional Chinese–to-English, Arabic-to-English, and for India, a Hindi-English bilingual dictionary.

Siri is also now able to answer questions about Indian festivals, and provides enhanced dictation in Hindi. Mojave also better addresses Hindi terminology to make the UI easier to understand.

Make no mistake, Siri still has serious issues understanding English. But learning to walk globally is likely more valuable than learning to run in a relatively limited market where perfect voice assistance isn't an extremely valuable or differentiating service.

Siri can be embarrassing in its ability to understand and respond to even basic requests.

The dramatic battle that wasn’t: macOS vs iOS

The idea that iOS is selling new Macs for development and content creation seems obvious, but strangely enough there’s an overwhelming populist media narrative that insists that Apple isn’t just successfully selling its Mac desktop and iOS mobile platforms, but is rather actually suffering from a directional, strategic crisis of epic proportions as it waffles between seeking to destroy its arms versus tearing off its legs.

Jobs once remarked that the then-new Mac OS X (based upon NeXTSTEP) would serve Apple for the next 15 years. Now named macOS, it's served as the default OS for Macs for longer than that, and has been the focus of all new platforms at Apple for more than 20 years. That in itself is incredible.

However, ever since iOS was split off as a mobile-optimized platform for iPhone and iPad, there’s been talk that maybe Apple would someday give up on the Mac, or alternatively find some way to shoehorn the Mac brand on top of an iOS device or somehow create a hybrid crossover PadPhone-Surface PC because that’s what all the other failed hardware makers are taking wild stabs at, and Apple clearly takes all of its cues from imploding peers that are totally incompetent—at least in the minds of many tech media wonks.

At WWDC, Apple’s chief software architect Craig Federighi resoundingly clarified that it has "NO" plans to mix up some kind of hybrid “do-it-all” platform. With Mojave, Apple is further making it obvious that the Mac serves a clearly differentiated purpose and audience as a platform distinct from iOS (and watchOS and tvOS—when you add those in it just makes the whole macOS vs iOS thing sound over the top moronic).

However, that doesn’t mean that Apple’s platforms can’t share ideas. In fact, it would be super stupid if the company didn’t apply what it has learned across shipments of hundreds of millions of mobile devices to its desktop Macs. It’s been doing this from day one, bringing iOS innovations “back to the Mac” and taking Mac technologies mobile.

However, Mojave shifts this incremental cross pollination into a punctuated equilibrium event, where the modern Mac is no longer competing with Windows PCs for “switchers,” but is instead recommending itself as the powerful computing system designed for iOS users who want to be content creators.

After all, the best audience to sell premium Macs to are the hundreds of millions of users globally who pay a premium to get iOS devices, rather than the far less valuable base of consumers opting for cheap Windows knockoffs or low-end Chrome OS netbooks or cheap Android tablets.

That’s true despite the most frantic efforts of the combined editorial staffs of Bloomberg, CNET and the Verge to advance the media narrative that Apple’s Macs are super in trouble because of, say, Chrome OS being dumped on US education in meaningless quantities that have zero impact on individuals or the enterprise—both of whom are actually going out of their way to choose to use iOS devices.

I started writing in early 2016 that perhaps people should consider that Apple doesn’t really even have any real competition. That’s even more true today, two years later.

But the bottom line here is that Mojave is designed to make the Mac attractive to iOS users, not so much creating a Windows PC alternative; those low-end users are being shown iPads in their price range.

Last year, Apple devoted a lot of attention to iPad with new gestures for drag-and-drop multitasking in iOS 11 that turned the tablet into a functional workstation for many PC users with streamlined needs. This caused some grumbling that Apple had lost sight or interest in the Mac. If PC users are supposed to buy iPad Pro, who buys Macs?

But this year, Apple has focused macOS Mojave on making the full desktop Mac experience even more familiar and accessible to iOS users, without losing any focus on a hybrid-legacy goose-chase, an entry-level Mac-box or a low-end netbook running macOS.

Mojave is an invitation for users of the billion iOS devices out there to consider buying a MacBook Pro or iMac in order to do some of the things you can’t do on an iOS device—such as create iOS software.

The entire newsroom at the Verge is probably trying to come up a way to spin a dramatic narrative that Apple is now moving from hating the Mac to hating iPads, but the reality is that Apple is (as always) simply working to improve everything it sells so it can sell more of them. But make no mistake: it is most certainly marketing Macs to iOS users and iPads to lower-end PC and netbook users.

When you read those clickbait thought-pieces about how iPads and Macs are fighting to the death, think about how clueless you’d have to be to write up such garbage. Apple has two computing platforms that both make tens of billions every year, each vastly more valuable than any other PC or tablet maker, ever. It doesn’t have to choose between them. It clearly hasn’t been choosing between them since iPad shipped in 2010. Mac sales have grown in parallel the entire time.

Customers aren’t confused about what they want. And it's pretty obvious that Tim Cook isn’t befuddled about how to plan, build, ship, and sell iPads and Macs at the same time, because he’s been doing it for eight years now—as rival PC and tablet makers have all diddled about and dramatically failed to sell ether one, despite getting nothing but lavish adoration from the tech media that clearly doesn’t know shit from Shinola.

Apple’s new Mojave is macOS X’s Windows 95

That might sound insulting, and of course, there’s a lot those two do not have in common. But sometimes an analogy—even a constrained one—helps to illuminate the logic behind an unusual viewpoint. Let me explain.

Back in 1995, Microsoft owned the market for PCs running a shitty, complicated MS-DOS that looked as inaccessible and old-manish at the time as IBM mainframes did when PCs became the hot new thing a decade prior in the 80s. Microsoft rather artfully upgraded the DOS PC from a fast dinosaur into a reasonably quick, nice looking experience based entirely on the work Steve Jobs had started with the Macintosh and had continued with NeXTSTEP.

By pairing the modern, attractive work Jobs had created with its own serviceable Win16 platform for developers, and then marketing it past every other alternative—including its own reneged OS/2 partnership with IBM—Microsoft ended up with near total ownership of the most valuable layers of the PC, starting in particular with Windows 95 and continuing—with very little effort or innovation—deep into the 2000s.

Of course, apart from delivering the graphical desktop experience Jobs had developed to mainstream audiences, Windows 95 was total shit inside. After its release, Microsoft spent the next five years just trying to dump its MS-DOS underpinnings and shoehorn its PC users onto its more modern, Unix-like WinNT operating system—something it didn’t quite manage to do until Windows xp arrived in 2000.

Incredibly, across the next 18 years Microsoft has done nothing but dumb down Windows into its current form as the artless, budget-written Windows 10, which is as fun to use as a suppository. Using Windows 10 feels like Microsoft is punishing its user base for failing to buy Windows Phone. It’s like the opposite-bizarro version of Tim Cook talking about “User Sat” on an Apple conference call.

Across that same period of time, Apple took the original NeXTSTEP and turned it into a nicer experience for Macs than Windows PCs delivered. Well, across a third of that time. By 2007 Apple was largely finished making Macs better than Windows, and was ready to release a mobile version of “Mac OS X“ powering the then-new iPhone. By 2010 it launched iPad. Apple quickly created an installed base of this new, simplified “iOS” that was larger than Windows PCs

Apple's iOS was literally the definition of Disruption: offering over-served customers a simpler alternative that better met their real needs.

But while Apple pushed iOS as the world’s best platform for building new apps and making money, Macs remained the way to build most content for iOS. Apple’s Mac platform had long been powering movies, music, live performance and print art. Now Apple was creating a new medium for Macs to build content for: its own mobile devices. That App Store market became larger than Hollywood.

How does Apple now advance the Mac? Make it more complex and inaccessible, on a premium luxury tier above iOS devices? Why not just make it premium and luxury and make it less complex and more accessible, converting as many new iOS users as possible into Mac-savvy content creators?

That’s Apple’s Windows 95 moment.

Apple’s macOS Mojave doesn’t have to steal its look and feel (as nobody else has a better one than Apple’s own), and it doesn’t need to market itself past larger former partners (let’s get real: Android, Blackberry, Galaxy, Facebook, Pixel and Surface have some customers of their own but all offer little effective competition for Apple).

The new macOS Mojave borrows from the simplified, focused experience of iOS. Apple is working to make desktop Mac computing a more powerful version of the iOS experience, not just a more complex one.

This all flies in the face of what the rest of the industry is trying to do, starting with Android licensees (and now Google) working to add the needless complication of desktop windows to mobile devices, and continuing into the hybrid nonsense Microsoft is pushing with shitty tablets that transform into shitty laptops that cost more than a basic notebook PC that has none of the delusional engineering compromises of complex hinges and confusing mode changes.

It’s incredible how stupidly absurd this all is, matched only by the witless tech media who can’t manage to criticize anything foolish even when they’re soaking in it—but who can deliver 24/7 demeaning critiques of the only company that is doing the things that are making money.

It’s important to recall that 23 years ago, it was Apple doing the dumb stuff, listening to analysts give advice on how it should copy yesterday’s thing and license the Mac System Software to PC makers; how it should keep investing in pen computing despite the lack of real interest in the market; how it should be expanding into online services with eWorld and video game consoles with the Bandai Pippin and TV-integrated Mac hybrids and stuff like QuickTime VR that had no viable business model in sight.

Back then, the tech media generally approved of all of the pointless, directionless, strategically flawed things Apple was doing even as Microsoft’s Windows 95 appeared on the horizon and began obliterating any apparent remaining path forward for Apple.

However, the majority of the people in the tech media have never experienced anything other than writing up what other people tell them to write, so they have no framework for understanding how things actually work. Rather than listening to them talk now, take a look at what actually happened.

Steve Jobs’ BYOKDM was off by 2

In between the years of Apple doing profitless stupid things in the mid 90s and today’s Apple doing all the things that are making any money at all, there was a middle period of Apple making occasional mistakes and bets that failed to pay off dramatically.

Back in 2005, for example, Steve Jobs introduced the Mac mini, imagining that PC users would switch from their existing PC box to a small new Mac that used their existing keyboard, display and mouse, as in “bring your own” or BYOKDM. That didn’t happen.

Three years earlier in 2002 Jobs similarly launched Xserve, thinking that businesses might switch from their PC servers to new rack-mounted Macs connected to their same KVM switch and Gigabit Ethernet. That didn't happen either.

Instead of either one ever taking off, Windows PC users of the day incrementally adopted iPods, then iPhone, then iPad. Today, Apple has a massive platform of iOS users: an audience to whom it can far more easily market its Macs versus a decade ago when it was trying to sell Macs to mainstream users who largely owned Windows PCs—and who were not already sold on Apple’s model of affordable luxury.

With today’s Macs, there’s no need to BYOKDM. Both of Apple’s most popular Mac lines already ship with a display, keyboard and precise pointer (iMac and MacBook Pros).

The funny thing was, Jobs was only off by two letters. What actually happened was BYOD. Once the masses could choose an Apple mobile device at work, getting a Mac was an obvious next step. That’s what Apple has been working to facilitate in macOS, culminating in today’s Mojave.

Mojave’s step one is to make the Mac look new and cool. Step two: make it work even more seamlessly with iOS. Now Jeff Goldblum could chime in with “there is no step three!” But there is actually an endless staircase of efforts Apple is making to keep enhancing iOS and macOS as valuable platforms for developers and users. All of that effort makes buying a new Mac really effortless for iOS users.

The New Mac

This last year I attempted to profile my mother, who is now 83, as a primary candidate for using an iPad Pro. Despite my suggestions, she asked instead for a MacBook, and being that I’m her kid and she bought all my computers before I was making any money, I got her a high-end 15 inch MacBook Pro with Touch Bar, a little concerned that she’d find it excessive and complex. She didn’t. She loves it.

Mojave will only make her machine easier to use, and even more familiar to work with next to the iOS devices she already has. Apple is making it easy for people in their 50s, 60s, 70s and up to buy a Mac. It’s making it easy for college students to buy a Mac. The company is taking full advantage of its massive success in mobile devices to market Macs as the desktop companion to iOS devices for everyone in between.

That’s something nobody else can do. Microsoft barely sells any PCs of its own. PC sales overall are flat or falling and have been for almost ten years. No Android maker can really promote an upgrade path to a well connected Windows PC. Samsung’s PC business has never been anything close to impressive. And most PC makers haven’t ever been able to successfully sell mobile devices.

So it’s important for the future of desktop computing that Apple is investing in macOS, building powerful systems that people will want to buy. There are very specific things many segments of the Mac world would like to see. Perhaps better chips from Intel that could address more RAM. Maybe keyboards that never fail and somehow remain thin while being large with a deep throw. There’s a lot that can be complained about Apple. But nothing compares to the experience Apple delivers in hardware and software, and that’s why individuals and businesses pay a premium to buy Macs.

If you’re worried that Apple was going to throw away Macs to focus on iOS, you can relax. Macs are following the same strategy of interactive enhancement that in retrospect is both strategically genius and also just competent work and artistic craft. Things are just moving a lot faster now.

Buckle up, the future is coming in hot.

Welcome to ⑆ RoughlyDrafted