Pro Display XDR and Apple's Grand Stand

The internet lost its mind in June when Apple's VP of hardware engineering John Ternus debuted the company's new Mac Pro and Pro Display XDR. For professionals, it was because of the bold new leap Apple was making to support real pro workflows. To content bloggers, it was an outrage that Apple's new $5,000 display dared to ship separately from its bespoke $999 aluminum stand. How dare Apple charge so much without some elaborate scheme to hide the real price?

The rear of the Apple Pro Display XDR, with stand at WWDC 2019

Grandstanding

Reporting and commentary on the new Mac Pro and its new Pro Display XDR was quickly drowned out by internet commentators all announcing that they had a hot take on why Apple was way off base to mention the price of its Pro Display XDR monitor stand. Principally: consumers were watching! What might they think? Surely the solution was simply to hide the price so nobody would find out.

There were lots of dumb takes. Engadget climbed on a soapbox to proclaim "A $999 monitor stand is everything wrong with Apple today. It's an expensive gadget nobody needs." The Verge stayed on brand with "Apple's $1,000 Pro Display XDR stand is the most expensive dongle ever."

Sam Rutherford of Gizmodo pleaded, "How Ridiculous Is Apple's $1,000 Monitor Stand, Really?," actually writing that its price "could be used to purchase a brand new iPhone XS, a new 4K TV (or two), more than three Nintendo Switches" or as one meme suggested, a few textbooks.

9to5Mac chimed in with "Apple's $1000 monitor stand is a massive (and unnecessary) PR fail," explaining that Apple should have just added $1,000 to the cost, which nobody would have really objected to.

Perhaps people who didn't need the stand might object to paying an extra $999?

The obvious reality is that the market for Pro Display XDR is effectively limited to professional users working in a studio where there are likely already custom VESA mounts installed for reference monitors. Some units are also going to be used by people in other settings where being able to effortlessly adjust and position the screen is important.

The choice to pick either a VESA mount or the stand Apple designed makes a lot more sense than inflating the price with mutually exclusive optional items, and then allow them to be removed—all just to cater to an audience that isn't even remotely close to buying a $5,000 display for a $6,000 and up workstation.

This adapter allows Pro Display XDR to fit a standard VESA display panel mounting system

If the problem is the optics of price, the least perceptive solution one could share is that the price should be raised for everyone just to coddle people who aren't remotely likely to buy it. That's incredibly dumb to say out loud.

A look behind the memes

A variety of memes lampooned Apple's monitor stand and everyone near it. In the one below, a photo taken by Business Insider was used to suggest that various people were captivated taking photos of the stand all by itself—as if monkeys excitedly hooting and waving their sticks around the Monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Image by Business Insider suggesting everyone is taking photos of a blank stand

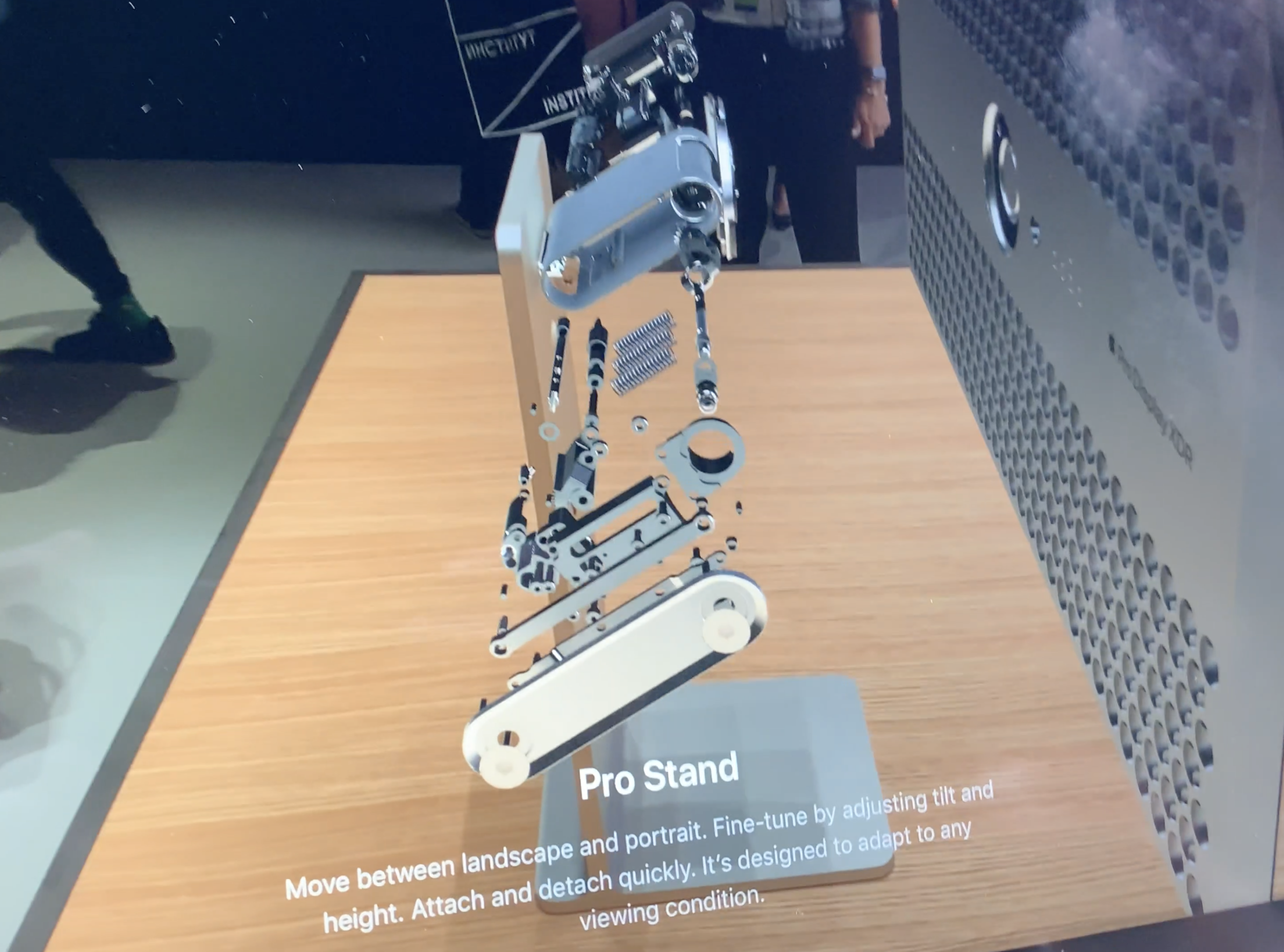

In reality, Apple had positioned the stand on a table by itself in the hands-on area to show off its Augmented Reality experience running on iPads. Holding up an iPad, observers could graphically explore the inner workings of the stand's counterbalance mechanism as well as the layers of the Pro Display itself. I appeared in the photo because I was trying to capture the iPad's AR presentation of the inside of the counterbalance mechanism with my phone.

The stand isn't just an expensive piece of metal; it's a counterbalanced, repositionable precision arm mechanism designed to allow the display to turn vertical or horizontal, and slide up and down effortlessly, holding its position exactly where it is set. Anyone who thinks that the stand isn't correctly priced should simply refuse to buy it, like its a Google Pixel 4 or a Zune or Surface or an Xserve. That's how markets work. Products that don't sell eventually stop getting produced.

Apple's AR tour of the inside of Pro Display XDR | via GIPHY

Beyond needing a custom design to make attachment of the heavy and delicate Pro Display possible, the stand also needs to be strong enough to securely hold a $5,000 or $6,000 display panel. This wouldn't be the smartest place to cheap out with a "commodity friendly, good enough" stand designed to hold up a lightweight TV panel. But does this mechanism need to cost $999, the same price that iPhone X debuted at when it was the state of the art in handheld mobile computers?

An entirely different market

Some sources have commented that the pro market Apple is now again targeting—after a years-long period of absence following the misfire of the 2013 cylindrical Mac Pro—doesn't seem to care too much about pricing. A review of other pro equipment seems to indicate that: seemingly simple brackets and other custom hardware easily cost thousands of dollars.

User RagnarKon commented on Reddit, "I used to work for a pro-video house, one of the last orders I made was for the Sony F-55 4K camera. Below is the breakdown:"

"Camera body: $29,000

Set of prime lens: $86,000

Memory cards: $7200

25" Monitor: $26,400

7" viewfinder monitor: $2900

Remote control panel: $1600

Misc Accessories: $9800

Heck... we paid $3000 for a piece of cardboard with colors on it. A $1000 monitor stand is a fricken bargain in that world."

It's not just that high-end pro users are willing to pay more. They are paying for different product tiers. Sony's F-55 camera is not a commodity 4K home camcorder. It's designed for an entirely different pro audience. It's not surprising that a Bobcat costs far more than a light-duty golf cart, despite both having four wheels. They are built for entirely different tasks.

It is, however, surprising that Apple could compare its new Pro Display XDR to a Sony reference monitor that costs $43,000, which it said still didn't "match the feature set of Pro Display XDR" priced at $4999, as the company detailed in its introduction of Pro Display XDR this summer.

Oddly enough, none of these tech bloggers compared Apple's Grand Stand to a Windows 10 Server standard license, which costs a grand just for a software license copy that costs Microsoft nothing to create. Perhaps Apple should give away the hardware and charge pro users a license fee for the intellectual property that went into designing it. Then it could also charge client access licenses per person who touches the thing. That would be so much easier for consumers to understand, and so much more lucrative for Apple.

Instead, bloggers like IGN Executive Editor Josh Norem compared it to a Playstation 4 with a consumer gaming TV and some video games. Really, why make movies or create soundtracks when you can play Spiderman?

Thousands vs millions

Beyond the qualitative aspect of pro-class hardware, there's also another factor: scale. High-end cameras, displays, and their accessories are very expensive not only because they are "better," but also because they are serving a smaller audience.

There are fewer potential pro users to bring the prices of their equipment down. Limited production runs are more expensive to build, distribute, and sell. That's an entirely different business from the consumer market that Apple has typically served.

From the Macintosh to iPod, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and HomePod, Apple's consumer products have often appeared to be premium, expensive products. The reality, however, was that Apple was taking very expensive technology and making it much more affordable by creating a mass-market product that could build and sell by the millions. Working in that volume brought the price down due to economies of scale.

A major component of Apple's high volume production of iPhone, iPad, HomePod, Apple Watch, and Apple TV has been the development of Apple's own proprietary silicon. While extremely expensive to design, once the cost is spread across the hundreds of millions of devices Apple sells, this custom silicon ends up as an extremely valuable differentiator that enables the company to build more advanced products and lower cost.

The delicate balance

Every year, Apple has been able to sell the previous year's iPhone at a significant discount because the perpetual push toward more advanced technology also helped previous generations of components become cheaper to build. Google has shifted its weight back and forth in consumer gear, pushing advanced Honeycomb tablets that were more expensive than iPad, then trying cheaper Nexus tablets, then going back to premium-priced gear. That hasn't worked out well.

Apple has maintained a much more stable focus on what it has tried to sell. Rather than boiling prices of PCs and phones down to the cheapest possible price tiers, Apple has maintained a target on a sweet spot in pricing that allows it to deliver better technology with more fit and finish integration, smarter software, higher-quality screen calibration, better quality audio, and more advanced features and security protections. This has established Apple with a more trusted brand than any other mass-market consumer electronics maker.

That's a very delicate balance to maintain perfectly over time. In some cases it appears Apple has pushed too hard and too fast, resulting in ideas that didn't work out as expected. For example, the push to make Thunderbolt the main connectivity protocol worked pretty well for MacBook Pros, but wasn't as well-received as a solution for the 2013 Mac Pro, necessitating a return to a larger tower with more PCIe slots and extra power and bandwidth allocations. The butterfly keyboard design that was created to deliver an ultra-slim Retina MacBook introduced unanticipated new problems of its own. Incremental fixes helped, but Apple ultimately moved to a new keyboard design to deliver the level of quality and performance it wanted to offer.

In software, Apple has worked to balance the demands for faster support for new features, for feature-parity and compatibility with other systems, and its efforts to deliver differentiating features such as secure Touch ID, Augmented Reality, Metal graphics, computational photography, and support for powerful gestures. Yet when these improvements—and the foundational changes that support them—aren't managed perfectly, users experience interruptions, bugs, instability, and security flaws.

This year's macOS Catalina and iOS 13 were both widely regarded as noticeably less reliable and stable than previous releases. The obvious solution is to hold back progress, but that in itself is also a problem. When Apple held back advertised features such as iCloud Drive sharing, the complaints were about as bad as if it had released unfinished features in perpetual beta in the model of Google—or perhaps even worse.

A similar engineering decision exists in the area of deciding what new markets Apple expands its efforts into. Does it dump out a more confusing, duplicative range of new products on consumers, from even larger phones to even smaller tablets? Does it start making TVs? Does it create $200 HomePods to rival the tide of $30 loss leaders from Amazon? Does it create $10,000 to $20,000 pro workstations that could only possibly sell to an audience of perhaps hundreds of thousands of professionals capable of earning a profit from high-end gear? What if that requires building accessories too expensive for the typical iPhone user?

Apple's loudest critics are nearly always on the wrong side of reality. It's not because they are bad people. It's just because they don't know anything.