How Apple beat Samsung in the 2010 global ARM race

Apple hasn't been outpacing Samsung in mobile Application Processor design over the past decade simply due to a first-mover advantage or by just having smarter people designing its silicon. Here's a look at how Apple first snuck past a larger and more entrenched silicon rival to gain its lead in advanced mobile chips, and why it matters to the future of tech.

Apple started a silicon revolution with A4

Apple's lost and found ARM

Long ago, Apple worked with British PC maker Acorn to deliver the original mobile ARM architecture in the early 1990s. But after sales of its ARM-powered Newton Message Pads failed to materialize, it liquidated its internal custom silicon design team as it limped through the end of the decade. By 2001, Apple was entirely reliant upon others to deliver the ARM chips powering its iPods.

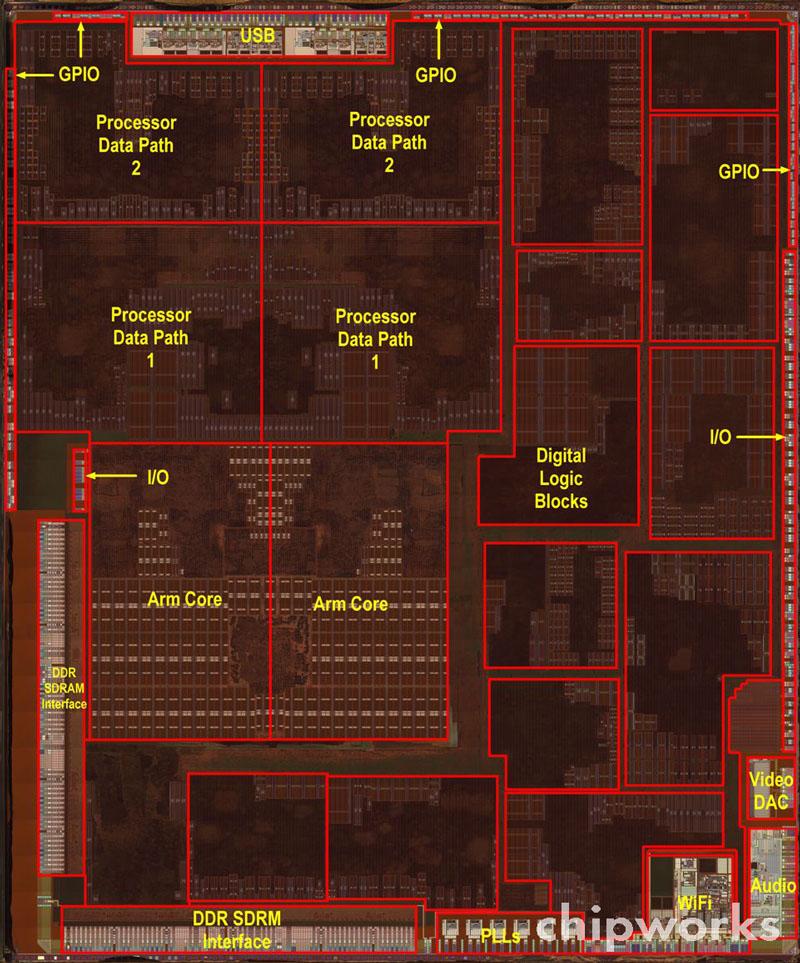

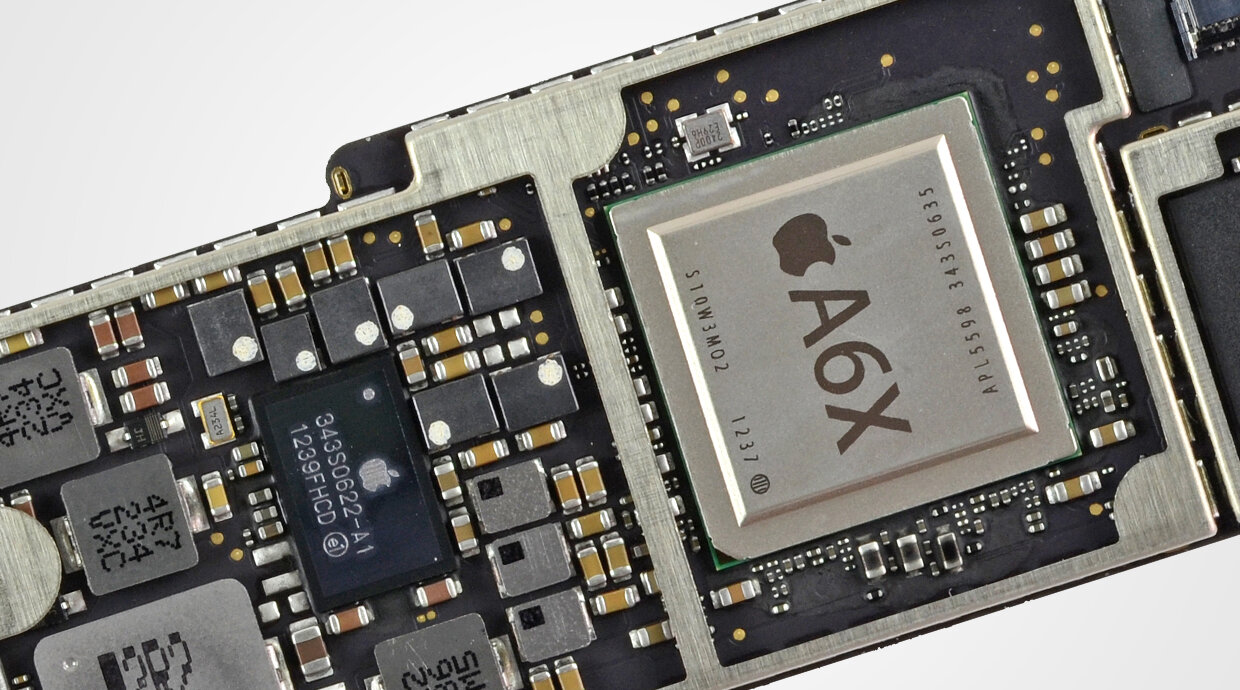

By 2010, the iPod had solidly turned around Apple's fortunes. Sales of new mobile devices also helped the company identify silicon mobile processors as a key technology it needed to develop and maintain on its own to be competitive. It acquired chip design teams and partnered with Samsung to deliver a new, much more powerful "Hummingbird" core it used its A4 chip, which it paired with the best mobile GPU available, Imagination Technologies' PowerVR.

Samsung also used the Hummingbird core and PowerVR GPU in its chip, which was later branded as "Exynos 3." But rather than seeking to relentlessly advance its custom chip design technology in the pattern of Apple, Samsung initially took the more comfortable and affordable route of relying on ARM to deliver its Cortex-A CPU and Mali GPU designs. That didn't work out well.

Even within 2010—when both companies had equal access to the fast new Hummingbird silicon that Apple had envisioned, developed, and funded in its partnership with Samsung—Apple managed to stage a coup that dramatically repositioned everyone in the consumer technology space.

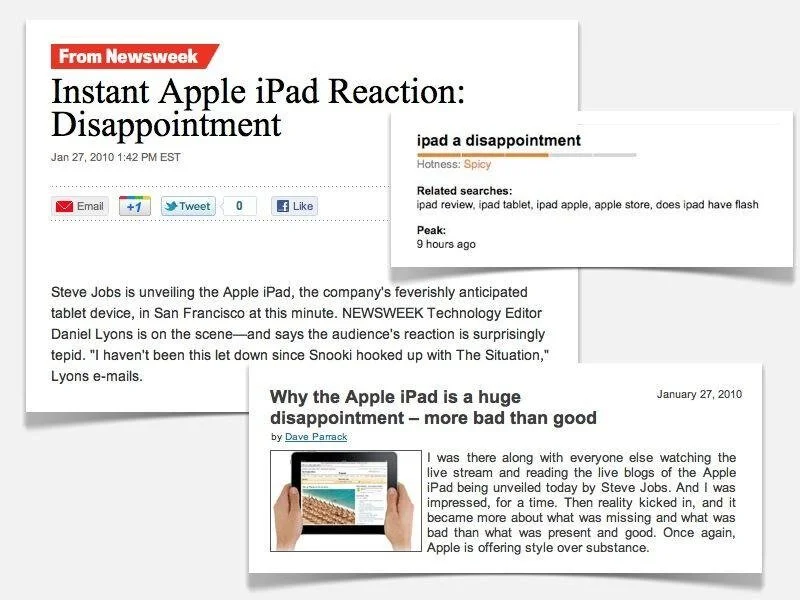

Apple iPad mocked at launch as Android phones draw attention

The tech media had largely doubted that Apple's newly-unveiled iPad would find an audience when it first arrived early 2010. Instead, there was more attention being devoted to all of the smartphone competitors that had arrived to take on iPhone after its first three years of radically changing the mobile market.

Most journalsits failed to grasp the potential of iPad at its launch

That included Google's new late-2009 partnership with Motorola to deliver the Droid phone, powered by a Texas Instruments OMAP chip. Droid wasn't just another phone, it was seen as a strategic weapon wielded by Verizon, the largest U.S. carrier, as a replacement to battle Apple's iPhone exclusive to AT&T after RIM's Blackberry had proven to be unfit for the task.

A few months later, Google introduced the HTC-built Nexus One using a Qualcomm Snapdragon chip. Nvidia had also just demonstrated Android running on its Tegra 2 chipset. With so many chip architectures and hardware manufacturers on board with Google's Android in phones, it seemed impossible for many journalists to think that Apple—still a minority player in smartphones behind Nokia's Symbian and RIM's Blackberry—could stay alive in phones, let alone in the Microsoft-dominated tablet market it was now entering.

It didn't seem important to many tech journalists that Apple was generating far more profits from its sales of iPhones than the phone industry's unit sales leaders were from all of their shipments of handsets.

Apple was not leading smartphone unit sales when it launched iPad

It was also well known that tablets had gone nowhere over the previous decade of Bill Gates' attempts to deliver Tablet PC starting in 2000, or in the decade before that when Apple was trying to sell John Sculley's vision of the Newton tablet across the 1990s. But by 2010, smartphones were recognized to be an important, high growth market with vast potential.

Apple's A4 work powers the competition: 2010

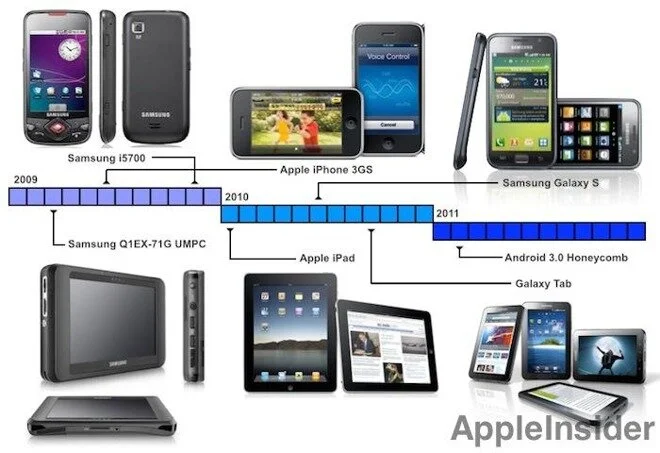

Further complicating Apple's prospects for iPhone and iPad was the fact that Samsung—its close partner in chips and other components—had started copying the surface of Apple's user interface and the outline of its product designs. A few months after the iPad appeared, Samsung delivered its first Galaxy S, which was styled to look like Apple's latest iPhone 3GS. It introduced its Galaxy Tab later in the fall, following the design of the iPad. Both products also used the same A4 chip design that Apple had co-developed with Samsung.

Samsung rapidly dropped its own designs to copy Apple's

In addition to using the "Hummingbird" Exynos 3 in its own new Galaxy Android devices, Samsung was also keeping its options open by using the same chip to also power its Wave smartphones running its internal Linux-based Bada OS in competition with Android. By the end of 2010, Samsung was also using the Hummingbird chip to power its Nexus S sold by Google as its official "how to do Android right" flagship. Samsung also began selling the chip to Chinese Windows CE maker Meizu for use in the M9, its first Android phone, in early 2011.

So the "A4" silicon technology Apple had assembled and funded to power a new generation of more powerful iOS mobile devices in 2010 was now also being made available to Samsung's own internal platform, to Samsung's own "Galaxy" branded copies of Apple's iPhone and iPad, to Google's Nexus brand seeking to compete with iPhone, and to Chinese cloners making modified versions of Android phones without Google's official blessing.

This wasn't widely reported at the time. Most contemporary accounts refer to all of these devices using "Hummingbird" chips from Samsung without any explanation of where for the powerful new class of ARM chips originated or what had financed it. The importance of this new technology that Apple had developed and financed from its massive, profitable sales of iPhone only started to become apparent as Apple continued to pursue independent silicon development more ambitiously than Samsung in the following year.

Leveraging A4 to deliver strategic apps for iPad

Across 2010, Apple didn't merely rely on A4 silicon to sell its new iPad and iPhone 4. It also immediately pursued establishing a software market for apps customized for iPad's larger display, leveraging the existing interest in the iPhone App Store. Neither Google nor any of its hardware makers saw any point in doing this, imagining that developers could account for scaling up and down apps on their own, without any centralized regulation guiding the development of app sales. This ended up being a tremendous mistake.

Apple had originally launched the iPhone without an App Store; it didn't even announce one until the spring of 2009, after Apple had sold over 3.7 million iPhones. Members of the media roughly criticized Apple for being so dumb as to think that "web apps" would be sufficient on iPhone, but nobody seemed to consider the fact that Apple was both ambitiously racing to get iPhone to market, and that it had already laid the groundwork in selling content in iTunes—including paid iPod games.

iPod Games quietly paved a foundation for the App Store

Apple had prioritized its iPhone hardware sales in part because there would be far greater return from iPhone sales than from any cut taken from App Store software sales. A functional App Store would also need a certain critical mass of sales to be able to capture and retain the interest of third-party developers. By the start of 2009, Apple had created an installed base of 3.7 million iPhone buyers who were excited to buy new apps for their phones.

A year later, Apple didn't have to wait a year for iPad buyers to reach a similar critical mass. In part, that's because iPhone had already established iOS as a platform and had created an audience of third party developers who were familiar with iOS. But on top of that, Apple also immediately sold iPad 3.3 million iPads in its first quarter of sales, establishing a second critical mass capable of supporting real tablet-optimized apps, not just stretched-out phone apps that could run on a tablet.

Across the September quarter of 2010, Apple sold 4.2 million more iPads, and that holiday quarter it sold another 7.3 million, resulting in first-year (nine months) of sales of 14.8 million iPads—a far faster start than even iPhone sales had experienced, and greater tablet volumes than all of Microsoft's Tablet PC partners had collectively shipped over the previous decade of trying.

The tech media incrementally began to grasp that their nearly unanimous dismissal of iPad earlier that year had been tremendously mistaken. But they steadfastly refused to consider that Apple might know what it was doing with its new App Stores built on a decade of leadership in content sales in iTunes.

Almost unanimously, bloggers kept disparaging everything about the App Store, from Apple's cut of revenues, to its curation "censorship" of porn and other content it didn't want to carry, to its "Walled Garden" refusal to support the side-loading of apps from other sources.

PC media pretends iPad isn't a thing

Almost as unanimously, tech bloggers also seemed to think that despite achieving unprecedented results in phones and then tablets, Apple's accomplishments up into 2010 would be easy for the losers in phones and tablets to catch up with and beat. Much of this thinking appeared to be rooted in the idea that consortiums of hardware and software vendors could deliver innovation faster than the vertically integrated Apple. That would also prove to be tremendously mistaken.

Apple's competitors also took notice of what the company was achieving and similarly seemed to think that, despite Apple's incredible launch of iPhone and iPad, competing with Apple would be rather easy.

For example, despite having witnessed the Windows Mobile smartphone platform being crushed by iPhone sales within just a couple years, Microsoft and its largest PC partner HP had attempted to derail interest in Apple's iPad by rushing out a prototype of Slate PC at CES just before Apple's iPad announcement. Their joint product looked terrible after iPad was announced, and even worse after it eventually shipped, achieving sales of just 9,000 units.

In fact, the appearance of iPad—and its radical departure from what Microsoft had been pursuing with its x86-based Tablet PC partners including Samsung and HP—pretty clearly motivated HP to immediately rush out and acquire the struggling Palm for its webOS—a new platform that appeared capable of powering phones and tablets using similar hardware to what Apple was delivering.

Samsung similarly set out to build an Android tablet that same year, abandoning its Windows Tablet history with Microsoft that had produced the thick Samsung Q1 "Origami" UMPC pictured above.

Yet despite Microsoft's largest tablet partners scrambling for the exits, the PC tech media couldn't quite admit reality. The clearly awful HP Slate didn't stop Tony Bradley of PC World from making excuses for the terrible product, insisting that the still undelivered Slate PC "is everything the iPad isn't--USB ports, expandable memory with SD card slots, support for Adobe Flash, able to run all of the software normally run on a Windows desktop PC. It's a 'real' computer."

The idea that iPad wasn't a "real computer" became a talking point that media research groups used to silo iPad sales away from Tablet PC sales, to help avoid any ugly comparisons of unit sales and market share, now that these figures were no longer flattering Microsoft or its Windows licensees.

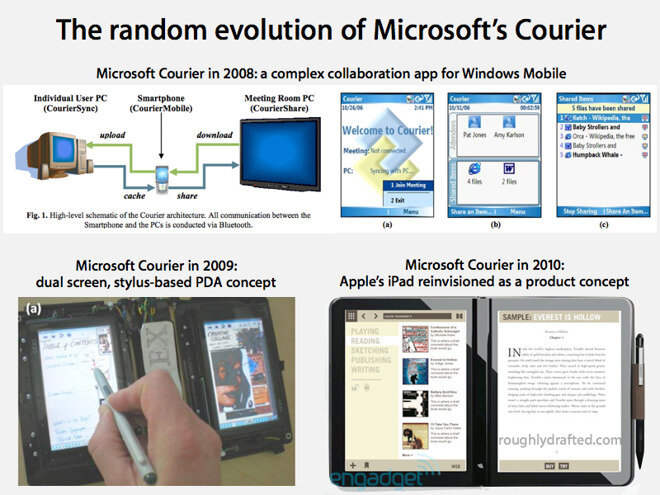

As excited as Windows bloggers pretended to be about Slate, they were even more excited about a purely "non-real" tablet computer: Microsoft's entirely vaporware Courier, which never even existed outside of renderings that portrayed it to be two iPads hinged together.

Microsoft's phony mockup of two iPads drew more applause from the tech media than the real iPad

Microsoft officially announced that Courier was being canceled just as iPad began selling in the spring of 2010, which should have been understood to be an admission that Courier was not anywhere near to being a real product. Instead, it was portrayed as being incredible magic that Microsoft simply lacked the courage to ship. Even a decade later, a variety of journalists keep holding up Courier as if it were a genius concept that is ready to take off as soon as Microsoft gets around to shipping it next year, running a completely different operating system.

Headless chicken strategies for iPad competitors

Since the early 2000s, Microsoft had pioneered early smartphone ideas with Windows Mobile in parallel to its decade of development on Windows Tablet PC. Apple had managed to rapidly crush any interest in either with the launch of the iPhone and then iPad. Unable to take on both at once, Microsoft effectively backed away from tablets in 2010 as its new Slate PC partnership with HP quickly fizzled and shifted into an adversarial one, with HP now pushing the idea of selling webOS phones, and soon, webOS tablets.

Microsoft decided to focus on the larger opportunity in smartphones, announcing a radical overhaul of its increasingly irrelevant Windows Mobile under the new name Windows Phone at the spring Mobile World Conference. Microsoft appeared so confident that its new Windows Phone 7 platform could finally stop Apple's advancement of iPhone that it staged a mock funeral for iPhone in the fall of 2010, before WP7 phones even arrived for sale.

Certainly, if Microsoft was arrogant enough to think people would dump iPhones to buy its new WP7 phones, it didn't lack any courage in deciding that Courier was unshippable vaporware that was completely unable to challenge iPad sales that were just getting started.

Incredibly, one of Microsoft's largest WP7 partners was Samsung, which had suffered along as a Windows Mobile partner alongside HTC. Even more astonishingly, Microsoft's reference platform forced Samsung to use Qualcomm's Snapdragon chips to power its new WP7 phones.

So despite having access to the new Apple-funded A4 "Hummingbird" chip, Samsung was paying its primary chip competitor Qualcomm, just to play both sides of the Android and WP7 platform war, even while trying to introduce its own Bada phone platform. And for good measure, it would also literally begin arming its competition in China with Hummingbird chips a few months later. Samsung's strategy appeared to be operating without any strategy.

Apple's iPad, and its jaw-dropping success at launch that just kept building throughout 2010, also prompted Google to radically rethink its own mobile strategy. Just three years earlier, the arrival of the iPhone had embarrassed the work Google had been internally doing to deliver a Java-based button phone. The company rapidly switched from copying Blackberry to turning Android into a copy of the iPhone, and by 2010 had achieved significant progress in establishing phone partnerships.

Google dropped everything to copy iPhone, then dropped that to copy iPad

But rather than focusing its efforts on phones as Microsoft had, Google slammed the brakes on Android phone development to radically pivot its attention exclusively to the development of new Android tablets it thought could stop the growth of iPad starting as soon as 2011.

Samsung, by far the largest Android licensee, independently rushed even faster to deliver its first Galaxy Tab, a smaller "tweenter" sized-tablet that not only borrowed Apple's iPad design but could also use the same co-developed A4 chip Apple had developed for iPad and iPhone 4.

Samsung was using Android 2.2 "Froyo" to power it, but that went against Google's wishes, as Google wanted to take on iPad in 2011 with an industry-wide blitz harmoniously using its new Android 3.0 Honeycomb designed specifically for tablets.

Themes that would continue throughout the 2010s

The media narrative that insisted that Windows or Android consortium partners would all march in lockstep to defeat Apple turned out to be entirely false. Within just 2010, Microsoft's stumble with Slate PC sent its two largest partners out on their own to work in direct competition with Windows, while Google's largest partner flipped it the bird on tablets simply because Samsung thought it could beat Honeycomb partners to market.

In reality, Apple wasn't competing with Android and Windows, it was competing against a series of the same companies that had failed to rival iPods, were failing to sell real iPhone competitors and were unable to deliver something competitive with iPad. Yet rather than admitting this, the tech media has consistently just parroted off wild claims by executives at Microsoft, Google, and their licensees that insisted that there was no possible way Apple could compete against their tightly cohesive, global partnerships.

From 2004 to 2007, Apple's annual gross profits increased 350% from $2.4 billion to $8.5 billion, then ballooned more than another 300% to reach $26.7 billion in 2010. Yet Apple was still being characterized as a minor player trying to compete in a world supposedly dominated by Microsoft or Google.

Within just 2010—the first year of Apple's ambitiously new A4 silicon—the company managed to flatten the playing field in tablets and establish iPad as a viable tablet-optimized app platform with the largest installed base of tablet users. It also demonstrated that it could radically innovate in hardware with the new iPhone 4, which was so successful as a product that it killed Verizon's hopes of exclusively using Android and convinced it to become an iPhone carrier subject to Apple's rules by the spring of 2011.

But more importantly, Apple's profits from 2010 were aggressively invested it making better products, crucially including new A-series silicon. Microsoft hoped to ride Qualcomm Snapdragon to success in phones using WP7, and later added support for Nvidia's Tegra. Google similarly delegated silicon to its hardware partners, hoping that between TI, Nvidia, Samsung, and Qualcomm, somebody would figure out how to deliver faster and more powerful chips than Apple. That turned out to be disastrously wrong, as the next segment will detail.